Introduction:

The 55th Session of the UN General Assembly adopted the Millennium Declaration, endorsed by 189 countries, as a ‘new global partnership to reduce extreme poverty’ to be reached by 2015 (UN, 2000: pp.1-5). The following year, in 2001, the UN declared a road map restructuring the Declaration in eight important goals, the Millennium Development Goals (UN, 2001: pp.18-19). The Declaration was accepted as a shared responsibility of the world to strengthen the values of human dignity and equality at the global level. It was a systemic shift from economic growth to more on human development and human well-being (Fukuda-Parr et al., 2014a: pp.3-4). The Declaration not just outlined the importance of lasting peace, respect for human rights, fundamental freedom, equal rights of all but also set an important target of halving the world poverty by 2015. Goals were not just limited to economic growth, as highlighted by Fukuda-Parr, it was also to realise that economic inequality poses serious obstacles in addressing the structural causes of poverty and thereby diminishing the efficiency of human capital (DESA, 2007: p.35). Despite being separate in concept, human development (focus on human capabilities) and human rights were integrated into a crucial framework of the Declaration.

Goal 1 of the MDGs was aimed at halving the extreme poverty by 2015, and $1 was set as a measurement to assess the achievement. The simplicity of the MDGs was a key attraction to address some of the most pressing human needs in the twenty-first century; human rights and capabilities. Sen (2005: pp.162-163) emphasised that human rights and human capabilities could go well together as long as one was not entirely ‘subsumed’ within the other. To further elucidate the integration of human rights in the Declaration, a set of guidelines were developed emphasizing the human rights and fight against poverty at the ‘very heart’ of UN system and further defined poverty as ‘the denial of a person’s rights to a range of core capabilities’ (OHCHR, 2006a: p.2).

The simple, measurable and limited number of targets and indicators also attracted many criticisms from experts and practitioners working in poverty reduction and development sectors. While many such criticisms focused on the minimalist approach of $1 a day and its limitation to ensure decent and promising life, some also feared that MDGs were based on the denial of justice and equality across geographies and would even widen the gap between wealthy and poor. The article reviews the different arguments; acclaiming the MDGs as a key driver in securing global attention to extreme poverty, attributing MDGs for overriding other vital development policies and needs, and the challenges of achieving first ‘global goals.’ The first part will review the strengths of the MDG in reducing extreme poverty, the second part weighs the imperfections in poverty reduction goal, and the third part will evaluate the achievements. While MDGs has been quantitatively successful in meeting its goal of halving the poverty, it overlooked the transformation of structural and institutional sources which create and sustain poverty in different forms.

Strengths and weakness of MDGs in reducing extreme poverty: Key arguments

There is no lack of institutions, experts and theorists who praise the MDGs as a simplified version of a global development policy built on unprecedented consensus (UNDP, 2003: p.1; Waage et al., 2010: p.995). Simultaneously, there are also a substantial number of critics aimed at improving the gaps in MDGs. Scholars, such as Fukuda-Parr, Yamin & Greenstein (2014b: p.4), believe that, regardless of the universality of the global goal-setting and targets being successful in forming and influencing the international development priorities, the interlinked consequences of the MDGs could not be sufficiently comprehended. They further enlarged that since the policy objective of the MDGs was to highlight unheeded social priorities, the goal of poverty reduction played a ‘broader role’ in defining development strategy, which, eventually, sidelined other important developmental priorities.

1. Strengths of MDGs in poverty reduction

MDGs were based on certain peculiarities not witnessed in the earlier phases of global development contexts. Core strengths of MDGs included the revelation of important social objectives in the form of concrete measurable outcomes (Fukuda-Parr et al., 2014c: p.4). The UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda praised the MDG framework for providing a global ’cause to address poverty and placing human progress at the forefront of the global development agenda’ (UNSTT, 2012a: p.6). Team also acknowledged that the MDGs focused on a limited number of real and shared development goals across the world.

Another strength of the MDGs was the focus on global partnership for development agenda. It linked the international collaboration with Official Development Aid (ODA) with a focus on aid, access to trade facilities and debt relief (OECD, 2006: pp.28-30). In addition to the ODA, additional $50 billion was needed to achieve the targets under the MDGs (Clemens et al., 2007a: p.736). The projection of $50 billion a year for the following 15 years did not include other conditions such as economic growth and improvement in national policies. Despite the deficit in keeping the international commitment in comparison to the Gross National Income (GNI) of the donor countries, the ODA increased from $53 billion in 2000 to $80 billion in 2004 and reached $133 billion in 2011 (DESA, 2012: p.5). Apart from the ODA funding, different other sources of development finance were also explored. For example, climate financing, small currency transaction tax, private contributions, and aid effectiveness were instrumented in the international development financing discussions and later reflected in various national and international funding streams.

Despite numerous critics, the MDGs accelerated an unparalleled progress throughout the world and as a result, have directly contributed to saving between 21 to 29 million lives and lifting 471 million people out of extreme income poverty (McArthur & Rasmuseen, 2017: pp.42-45). McArthur & Rasmussen resonate that extreme income poverty should be considered a ‘special’ issue of the MDGs and despite the poverty target being complicated to measure, all regions observed achievements in headcount poverty ratios since the MDGs were introduced.

The income poverty target of the MDG cannot be achieved in 15 years of timeframe given the unaccounted number of challenges fuelled by uneven world order, weak institutions, the absence of unified vision for equality across regions and countries and multidimensional characteristics of poverty. For example, over 200 million more people fell into the extreme poverty trap during 2005-08 due to the startling impact of fuel, food and financial crisis in 2008-09 (Hulme et al., 2010: p.299). Many random and unnoticed events could endanger any well-formulated policies identical to the MDGs. And despite a series of imperfections, if considered within a longer timeframe, the MDGs served as a reagent in transforming universal values that do not accept global poverty as ‘morally acceptable’, and consequently, the MDGs succeeded in altering the way poverty was interpreted and treated in international development policies (Ibid, p.302). Greenstein, Gentilini and Sumner (2014: pp.133-134) suggest that MDG 1, or extreme poverty goal, should not be accepted as an end of a ‘snapshot’ in time. Rather, the OECD’s international development goals (IDG), MDGs and post-2015 agenda should be perceived as an interlinked yet evolving process which allows global quest for collaborative action in addressing extreme poverty and exclusion. They further argue that poverty goal was ‘iterative’ process and prevented the world from having two sets of global targets; one stemming from the UN and the other from donor countries, i.e. OECD. The OECD had already defined international development goals, known as Shaping the 21st Century, in 1996 (OECD, 1996) which later integrated in the MDGs. Strategically, the MDGs did not transform the critical development issues, such as poverty reduction, in a simpler form. Reasonably, a set of ignored developmental issues were placed at the centre, and, as Poku & Whitman (2011: p.7) claim, more integral in the context of international and global development politics that is crucial to deal with injustices and exclusion which proliferate poverty.

2. Weaknesses of the MDGs in halving extreme poverty

The criticism of MDGs is not just limited to the core concept but also in the structures and implementation of the goals. Gore (2010: pp.70-71) criticised that the MDGs were a departure from ‘Keynesian’ approach of development to ‘Faustian bargain’. Faustian bargain is a kind of contract or bargain in which a person sacrifices his moral, ethical or spiritual values in favour of wealth, power or other benefits. Gore further elaborated that international development during the 1960s and 1970s was founded on a Keynesian development consensus when economic growth in the South led to the increase in the import capacity of developing countries which supported the achievement of full employment opportunities in the North. But the low inflation in the early 1980s ended mutually-beneficial interests resulting from a search for ‘new’ consensus, or Faustian bargain, that underlined the MDGs, and eventually produced two major shifts. First, the swing away from development of national economy to individual lives; meant the shift from addressing the inequality gap between industrial and developing countries to poverty and human development. Second, the MDGs adopted the minimalist approach of reducing the proportion of people living with less than $1/day by 2015 which was entirely focused on developing countries. The MDGs adopted a set of goals and targets that ignored the international discourse on reduction in income inequality across countries and societies and individuals’ income poverty superseded the need of national development and growth priorities.

Some even criticised the notion of income poverty as a complete departure from human rights and human capability principles. Indicators were more focused on material means rather than reflecting on the principles of social inclusion, justice and peace (Fukuda-Parr, 2013: p.15). The human development and human rights approach to development focused on people not as a beneficiary of development projects but a change agent in social relations and structures (OHCHR, 2006b: p.4). Unfortunately, the poverty measurement by $1 a day could not be enough to get humanised conditions to the poor people. This was basically due to the misinterpretation of different dynamics of poverty to income poverty ignoring various empirical evidences around the world.

MDGs were built on various development policies, such as the IDGs of OECD, and several studies were commissioned to inform the target and indicators. The World Bank-commissioned, a study, Can Anyone Hear Us? Voices of the Poor, that concluded five main concerns from the experiences of poor people; poverty is linked to interlocking ‘multidimensionality’, households are suffering from the stress of poverty, state has been largely ineffective in reaching to the poor, NGOs have limited capacity, and social support system for the poor is unravelling (Narayan et al., 1999: p.7). The World Development Report 2000/2001 highlighted three core areas to tackle poverty problem; promoting opportunity for poor people, facilitating empowerment by making state institutions more accountable and removing the social barriers as a result of discrimination, and enhancing security by reducing the poor people’s vulnerability to disease, disasters and violence (World Bank, 2000: p.vi). Three targets and nine indicators under poverty goal (MDG 1) largely overlooked the recommendations from these and other studies that poverty reduction would be utterly difficult unless the appropriate level of structural changes allows fair distribution of growth and income opportunities. As a consequence, the ignorance resulted in a form of uneven achievements of income poverty reduction and poverty ratio gap. The unintended consequences were pre-aligned to the poorly-defined targets and indicators largely overshadowed by the limited number of goals.

The UN later realised that the focus on a limited number of development goals underestimated broader development dimensions (UNSTT, 2012b: pp.6-7). The MDGs; a set of 8 goals, 21 targets and 60 indicators (UN, 2008), could not maintain similar focus and effects. Some targets were not robustly formulated, and some targets ignored demographic change causing an escalation of social problems. Goals were designed to be missed not because of the funding gap or other external calamities, but due to the way the targets and indicators were set (Clemens et al., 2007b: p.736). The goal of halving poverty by 2015 in many countries was practically impossible due to the high standard of growth ambitions. Although most of the costing exercises considered ‘financing gap’ in meeting the national growth targets, the approach lacked rationale ground and accuracy of cost calculation (Ibid, p.739). The financial gap had a direct effect on the outcomes. The fastest growing economies, such as China and India, met the target of halving poverty but it was almost palpable from the beginning that other parts of the world, and Africa in particular, would lag behind. In 2004, Africa was still the home of 34 out of 48 poorest countries in the world and would require over 7 percent of the GDP growth, annually, for the following 15 years to halve the poverty rates (IBRD/WB, 2004a: p.21). The requirement of 7 percent annual growth in the GDP was not just impossible for Africa, given the existing challenges, but even very difficult for other countries. Only five countries; China, Ireland, Liberia, Myanmar, and Vietnam, in the world achieved similar GDP growth rate during 1985-2002 (IBRD/WB, 2004b: pp.182-184). The ambiguity of 50 percent reduction in poverty population could mean cutting 80 percent in a country to 40 percent and 8 percent in another country to 4 percent. The absence of baseline or uniformity in the baseline, coincided with the changing nature of poverty population in the countries, drastically influenced the production of uneven achievements.

MDGs also failed in adequately addressing the challenges of productive employment, social protection, inequality and social exclusion let alone a violation of human rights and other political and natural disasters causing setbacks in the full realisation. Putting the national stakeholders in the driving seat, and tailoring the global goals according to national priorities had some benefits regarding local ownership and contextual adjustment of the target and indicators (Vandemoortele, 2011: p.14; Nayyar, 2013: pp.374-375). On the contrary, the limited guidance about the means to achieve the objectives ended up in expensive failures in addressing the root causes of poverty and other human needs. While national ownership was reflected in the MDGs, it rather bypassed the sub-national and grass root realities. Integration of local needs were critically required to establish a robust link between national targets and local results. Overvaluing global objectives disregarded the realities of national and local challenges causing unpremeditated, yet predicted, failure in many countries but notably in Africa. Unfulfilled international commitments to support the weak performing countries also played a key role in producing noteworthy variances across indicators and countries.

The international community did not fulfil many of the international commitments. Despite donor countries reaffirmation to increase ODA, many of them set the target at 0.7 percent of the gross national income (GNI) and extended 0.15-0.20 percent of the GNI as ODA to the least development countries, were not fully realized (UN, 2011: pp.9-10). Although the gap between commitment and action was realised earlier, not much materialised to help countries meeting their national targets.

3. Progress on MDGs target in halving extreme poverty by 2015

Developing countries as a whole met the MDG’s target of halving extreme poverty. Population living below extreme poverty line is calculated to fall to 13.4 percent by 2015, which is over two-third from the poverty percentage in 1990; 43.6 percent. East Asia and Pacific enjoyed the most remarkable achievement in terms of poverty decline whereas Sub-Saharan Africa still stands at the bottom of the list and is not expected to meet the target by the end of 2015 (IBRD/WB, 2015: pp.3-5).

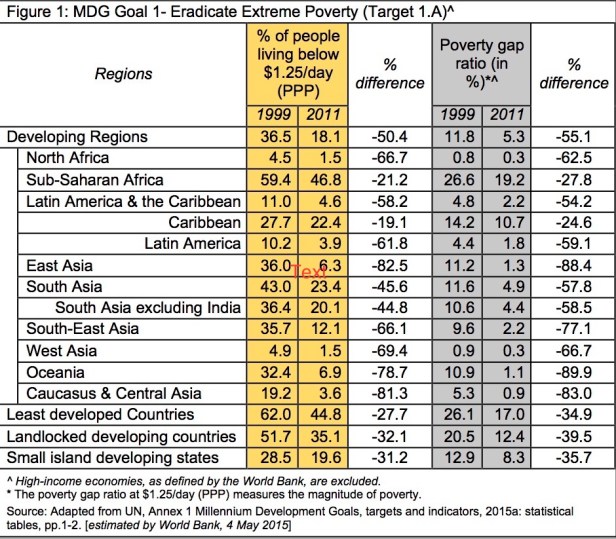

As highlighted by the World Bank, developing countries met their target of halving poverty ratio of the population living below $1 a day; from 36.5 percent in 1999 to 18.1 percent in 2011 (Figure 1). Within developing regions, the ratio of the population below poverty line reduction varied significantly. Eastern Asia along with Caucasus and Central Asia enjoyed the highest percentage of poverty alleviation, by 82 and 81 percent each, whereas the least improvements were witnessed in the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa, with 19 and 21 percent, respectively. On the contrary, least developed, landlocked developing and small island developing countries all failed in meeting the targets.[1] The lowest reduction in the population below extreme poverty occurred in the least developed countries, from 62 in 1999 to 44.8 percent in 2011 which is the lowest among all regions. Landlocked and small island developing countries could not succeed beyond 32 and 31 percent decrease in poverty ratio respectively.

Changes in the situation of poverty population also influenced the indices of poverty gap ratio but with distinct patterns. While Oceania observed 89 percent, Caribbean was limited to 24 percent positive change in the poverty gap ratio. Similarly, East Asia and Caucasus & Central Asia followed 88, and 83 percent decline in the poverty ratio gap whereas Sub-Saharan Africa remained at the bottom of the list, with 27 percent.

The UN claims, based on the projection, that the global extreme poverty population rate dropped to 12 percent as of 2015 (UN, 2015b: p.15). This decline is one percent more than the projection World Bank had earlier made. Furthermore, 1.9 billion people living in extreme poverty fell to 1 billion in 2011, and additional 175 million people stepped out of extreme poverty by 2015. China and India played a crucial role in helping the MDGs to meet its extreme poverty target by 2015; 61 to 4 percent decline in East Asia and 52 to 17 percent in South Asia. However, the UN further concedes that more than 80 percent of the total number of impoverished people live in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa and five countries; Bangladesh, China, DRC Congo, India, and Nigeria, host 60 percent of the 1 billion people living in extreme poverty.

Conclusions:

MDGs were certainly not free from limitations. However, no global policies could remain free from criticism and the need for improvement. Experts’ and scholars’ input have enriched the international development policy system with the need to include a wider segment of the actors and institutions, in determining international development goals, setting targets and enlisting indicators to deal with the global problem of poverty alleviation collectively. While MDGs met its goal of halving the extreme poverty, the results vary across regions and countries. The decline in absolute poverty had an impact on the decrease in poverty ratio gap, but the difference between the two indicators was disproportionately wide. Many countries could not show the achievement due to insufficient data. While income poverty decreased, income inequality widened. No doubt, the MDGs put the extreme poverty at the core of international development discourse. However, significant attention is required to ensure that not all international efforts ignore the rising inequality gap between rich and poor communities, and countries, due to silo focus on reducing the extreme poverty, measured by $1 or 2 a day. While vertical guidance and support can help national stakeholders readjust the global targets to best fit in local contexts, it is equally important that transparent and inclusive mechanism are put in place to avoid ad-hoc basis of policy formulation, discretionary implementation and customary review. It is never too late to learn from the empirical evidence of MDGs realisation in addressing poverty issue which can strengthen the fragile ground of post-2015 development goals. The cost of learning and integrating lessons in future poverty reduction policies is indisputably inexpensive than living with the uneven achievements and inadvertent consequences.

References

Clemens, Michael A., Kenny, Charles J. and Moss, Todd J. (2007), The Trouble with the MDGs: Confronting Expectations of Aid and Development Success. World Development, 35(5): 736-739.

DESA (2007), The United Nations Development Agenda: Development for All. : 35.

DESA (2012), World Economic and Social Survey 2012 In Search of New Development Finance. New York: United Nations.

DESA (2014), Country Classification. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2014: 144–150.

DESA (2016), List of Least Developed Countries.

Fukuda-parr, Sakiko (2013), Global Development Goal Setting As a Policy Tool for Global Governance: Intended and Unintended Consequences. Brasilia DF.

Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko, Yamin, Alicia Ely and Greenstein, Joshua (2014), The Power of Numbers: A Critical Review of Millennium Development Goal Targets for Human Development and Human Rigths. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 15: 3–4.

Gore, Charles (2010), The MDG Paradigm, Productive Capacities and the Future of Poverty Reduction. IDS Bulletin, 41(1): 70–71.

Greenstein, Joshua, Gentilini, Ugo and Sumner, Andy (2014), National or International Poverty Lines or Both? Setting Goals for Income Poverty after 2015. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 15(2–3): 133–134.

Hulme, David and James, Scott (2010), The Political Economy of the MDGs: Retrospect and Prospect for the World’s Biggest Promise. New Political Economy, 15(2): 299-302.

IBRD/WB (2004a), Strategic Framework for Assistance to Africa: IDA and the Emerging Partnership Model. Washington DC.

IBRD/WB (2004b), World Development Report 2004. Washington DC.

IBRD/WB (2015), World Development Indicators 2015. Washington DC.

McArthur, John W. and Rasmussen, Krista (2017), Change of Pace: Accelerations and Advanced during the Millennium Development Goal Era. Washington DC.

Narayan, Deepa, Patel, Raj, Schafft, Kai, Rademacher, Anne and Koch-Schulte, Sarah (1999), Can Anyone Hear Us? Voices from 47 Countries.

Nayyar, Deepak (2013), The Millennium Development Goals Beyond 2015: Old Frameworks and New Constructs. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 14(3): 374–375.

OECD (1996), Shaping the 21st Century: The Contribution of Development Co-operation. Paris.

OECD (2006), Development Co-Operation Report 2005.

OHCHR (2006), Principles and Guidelines for a Human Rights Approach to Poverty Reduction Strategies. Poverty Reduction: 2-4.

Poku, Nana and Whitman, Jim (2011), The Millennium Development Goals: Challenges , Prospects and Opportunities. Third World Quarterly, 32(1): 7.

Sen, Amartya (2005), Human Rights and Capabilities. Journal of Human Development, 6(2): 162–163.

UN (2000), United Nations Millennium Declaration. : 1–5.

UN (2001), Road Map towards the Implementation of the United Nations Millennium Declaration. , A/56/326: 18–19.

UN (2008), Official List of MDG Indicators.

UN (2011), The Global Partnership for Development: Time to Deliver. New York.

UN (2015a), Millennium Development Goals, Targets and Indicators 2015: Statistical Tables.: 1-2.

UN (2015b), The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. New York.

UNDP (2003), Human Development Report 2003 (Summary). New York, Oxford.

UNSTT (2012), Realizing the Future We Want for All: Report to the Secretary-General. : 6-7.

Vandemoortele, Jan (2011), If Not the Millennium Development Goals, Then What? Third World Quarterly, 32(1): 14.

Waage, J. et al. (2010), The Millennium Development Goals: A Cross-Sectoral Analysis and Principles for Goal Setting after 2015. The Lancet, 376: 995.

World Bank (2000), World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Poverty. New York, Washington DC: Oxford University Press.

[1] Countries with less than $1,035 GNI per capita are classified as low-income countries, those with between $1,036 and $4,085 as lower middle income countries, those with between $4,086 and $12,615 as upper middle income countries, and those with incomes of more than $12,615 as high-income countries (DESA, 2014: 144-150).

48 countries are listed as Least Development Countries, as of May 2016 (DESA, 2016). 31 countries are classified as Landlocked developing countries (http://unctad.org/en/pages/aldc/Landlocked%20Developing%20Countries/List-of-land-locked-developing-countries.aspx [Accessed on 28 March 2017]).

37 UN members are categorised as small island developing countries (https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sids/list [accessed on 28 March 2017]).