INTRODUCTION

The Constitution of Nepal 2015 adopts the federal form of governance system and so the elections of the HoR and PA are an essential component of federalising the country. While state restructuring in Nepal has remained as a continuous process for ages, the First Amendment in the Interim Constitution of Nepal 2007 in April 2007 was the first-time federalism formally integrated into the national statute.

On 21 August 2017, the government announced the date of the elections to the House of Representatives and Province Assemblies would be 26 November. Despite the government announcement, many people had no confidence in the timeliness of the polls. The level of suspicion around the polls was at its peak, and everyone was doubtful. Even the Election Commission (EC) was not assured of timely election. For these reasons, the EC also expressed its opinion to hold the polls in a single phase. Finally, the government on 30 August 2017 decided to hold elections in two phases: on 26 November in 32 districts of Mountains and high-Hills and on 7 December in 47 Hill and Tarai districts.

Elections of the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly in 2017 witnessed a mix of political developments in the country. The alliance between CPN-UML and UCPN-Maoist made a big surprise to everyone and also forced other political parties, including Nepali Congress, to form partnerships with others. Provision of minimum threshold (i.e. 3%) also compelled the political parties to work on alliances and some smaller parties even merged into one. While some groups and parties opposed the elections, confrontation, violence and IED explosion filled the citizens with a sense of fear whether the polls would be held as scheduled and whether there would be enough safety to cast votes. The government adopted various measures to ensure safety and security throughout the election period. Despite some incidents, polls completed without any serious obstacles.

Looking at the election engineering, Nepal adopts a mixed electoral system; First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR). Out of 275 seats in the House of Representatives (HoR), 175 represents FPTP and 100 seats under the PR system. Similarly, 330 seats are allocated to the Provincial Assembly (PA) under FPTP and 220 seats under PR. Positions under the PR were shared among women, Khas Arya, Dalits, Madheshi, janjatis, and backward regions. Seats assigned for the persons with disability and minorities were merged with Dalit or other groups. 5,182 candidates registered in the ECN to complete for 825 seats in the federal and provincial legislatives. Over 15 million voters registered to cast their votes. However, insufficient voter education resulted in a considerable number of invalid votes. Similarly, in addition to the Nepalese living or working abroad, security personnel, public servants and staff engaged in election management were also not able to cast their votes.

Although media and civil society organisations played crucial roles in providing information, encouraging discussion, and condemning acts of violence, public scrutiny and oversight over the electoral process, and election management, in particular, remained weak.

Despite some weaknesses regarding compliance with the code of conduct, accessibility issue in some polling centres, and violent incidents, the ECN succeeded in holding peaceful and comparatively free elections of the HoR and PA. Only five political parties secured the status of ‘national party’. CPN-UML emerged as the largest party at the federal level, and the Left Alliance secured a dominant majority in 6 out of 7 provinces. Nepali Congress shrunk to 176 seats against 525 seats of the Left Alliance in HoR and all seven provincial assemblies. Two Madhesh-based parties, FSFN and RAJAPA, 12 per cent of seats across the country, with a just majority in Province 2.

DISCUSSION

1. Political Context

The elections of the House of Representatives (HoR) and the Provincial Assembly (PA) were viewed as a major step towards the implementation of the Constitution of Nepal 2015. However, there were, and still are, historic and strategic significance behind those elections. Until 1990, the monarchy and the unitary system was blamed for poor service delivery and snail-paced reform process in the country. But, the mainstream political parties; namely Nepali Congress, CPN-UML, RPP and Nepal Sadbhawana Party, remained a key part of parliamentary politics since 1991, when the first People’s Movement forced the royal palace to restore multi-party democracy. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) 2006 and the Interim Constitution of Nepal 2007 raised high hopes among the ordinary citizens, in general, and the marginalised communities, in particular, that the new constitution would bring a robust legal environment to help drive Nepal towards a more inclusive, accountable, tolerant and progressive society.

The elections of the Constituent Assembles in 2008 and 2013 provided a great opportunity to the political and civic leaders in the country to reflect people’s aspiration in the constitution writing process. Maoists and Madhesh-based parties emerged in the political landscape as ‘kingmakers’ since the election of the first Constituent Assembly in 2008. Two rounds of elections and operations of the Constituent Assembly (CA) consumed abundant time and resources to explore, interact and negotiate an amicable model of federalism in the country. However, political negotiations, influenced by number game in the CAs, ended up with a majority-led constitution in September 2015 (Haviland, 2015). The dissatisfaction of a number of social and political groups over some elements of the constitution observed bloody confrontation before, during and after the promulgation of new Constitution (ICG, 2016). Within 126 days of its promulgation, the Constitution was amended for the first time (Koirala, 2016) on 23 January 2016 focusing on proportional inclusion and delineating of electoral constituencies. Another attempt of amending the Constitution for the second time failed on 21 August 2017 as the bill could not get enough votes (Ghimire, 2017). The ruling coalition and agitating Madhesh-based parties continued negotiations until the very last days before the elections.

On 20 July 2017, the government formed an Electoral Constituency Delimitation Commission to propose the delineation of federal boundaries for the purpose of provincial and federal elections. The Commission submitted its report to the government on 30 August 2017 with 165 constituencies across the country. Constituency delineation was based on two aspects; geography and population with 90 percent weightage to the latter (Giri, 2017). Madhesh-based parties expressed their concern as the delineation could not satisfy their demands. But, the Election Commission of Nepal (ECN) moved forward. Despite their reservation Madhesh-based parties later participated in the elections.

In the meantime, and to everyone’s surprise, the CPN-UML and the UCPN-Maoist announced to participate in the elections as an alliance, Left Alliance, and later unify both parties after the elections. Nepali Congress also formed another one, the democratic alliance. As a result, smaller parties felt the threat and merged or formed alliances to be able to meet 3 per cent threshold to remain a national party. Difference between larger and smaller parties and their alliances were observed regarding organising rallies, publicity, media coverage and dominance in election campaigns. While bigger parties organised events across the country, smaller parties were limited to specific constituencies and in social media.

To deal with increasing threats, confrontation and violent incidents, the government classified electoral constituencies and polling centres into highly sensitive, sensitive and normal based on security threat assessment. Over 200,000 security personnel were deployed, and hundreds were arrested for their involvement in anti-poll activities. But, despite those incidents, the elections of the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly were held successfully laying the foundation of parliamentary democracy in a changed political context, i.e. federalism.

2. Legal Framework

Nepal is a party to several international instruments that demand free and fair elections. These instruments include, but not limited to, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities (UNDM), Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), UN Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) General Comment 25, UN Convention Against Corruption, and the Charter of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). Nationally, periodic elections are integrated as a crucial element of democratic norms and values the Constitution of Nepal 2015 envisions to promote under its commitment to socialism. Freedom to form political parties, freedom of opinion and expression and prohibition of discrimination based on ideology are guaranteed under Fundamental Rights in the Constitution (Article 17 and 18).

Regarding the elections of the House of Representatives, the Constitution of Nepal 2015 integrates composition and terms under Article 84 and 85 (NLC, 2015). 275 members constitute the HoR. Of the 275 members, 165 members get elected through First-Past-The-Post (FPTP)- one from each of the election constituency across the country. Remaining 110 members get elected through Proportional Representation (PR); the whole nation as single election constituency and voters cast a vote to the political parties. On the other hand. The composition of the Provincial Assembly includes two types of members (Article 176). 60 per cent of the members refer to the number twice as many as the number of the HoR members from the respective province through First-Past-The-Post (FPTP), and 40 per cent of the members should be elected through the proportional representation (PR) system.

Regarding the right to vote and right to stand in the election, each citizen of Nepal has the constitutional right to cast a vote in any election provided that s/he has completed the age of 18 years. The Constitution of Nepal 2015 also guarantees the right to stand in elections. Article 87 of the Constitution of Nepal 2015, also reiterated by the House of Representative Election Law 2017 under Article 12, sets the eligibility criteria of the candidate (ECN, 2017a). A person who is a Nepali citizen, having completed the age of 25 years, not convicted of a criminal offence involving moral turpitude, not being disqualified by any federal law, and not holding any office of profit is considered eligible to stand in the election of the HoR. Similarly, Article 178 of the Constitution of Nepal 2015, also reiterated by Article 12 of the Provincial Assembly Election Law 2017, determines the qualification of the candidate (NLC, 2015; DoP, 2017). A person is eligible if s/he is a citizen of Nepal, a voter of the concerned province, has completed the age of 25 years, has not been convicted of a criminal offence involving moral turpitude, is not being disqualified by any law, and is not holding any office of profit.

To ensure that the entire electoral process is free of abuses and manipulation and there are remedies available, the Election (Offences and Punishment) Act 2017 is endorsed to provide a legal basis. Voters, candidates and personnel mobilised for the election purpose are provided with dos and don’ts. The Act also provides the right to appeal the decision or the result. The Act elaborates causes, processes and consequences of any offence made against the electoral law or the process. It consists of offence and punishment related to abuse or misuse of election materials, violation of voting and voting process, influencing election staff or the voters, violating established code for campaigning and funding for the electoral campaign. It Act prohibits the staff, security personnel and monitors from using their access and influence to manipulate the electoral processes or confidentiality. The Supreme Court is assigned to hear and decide on cases related to the elections of the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly. For the election purpose, the Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court was assigned to hear and settle any cases related to the elections of the HoR and PA.

2.1 Electoral System

Nepal adopts a mixed electoral system; First-Past-The-Post and the Proportional Representation (DoPa, 2017). First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) refers to the voting method in which the candidate receiving the most votes win the election in a single electoral constituency of the HoR or the PA where applicable. FPTP consists of 165 seats in the HoR and 330 seats in total in all 7 Provincial Assemblies. On the other hand, the Proportional Representation (PR) refers to the voting method where voters cast a vote to the political parties considering the whole country as one electoral constituency and by received votes, the political parties select the representative for the HoR. 110 seats are allocated under the PR system in the HoR and 220 seats in total in all 7 Provincial Assemblies.

Representation under the PR in the HoR includes a closed list of women, Dalits, indigenous nationalities, Khas Arya, Madheshi, Tharu, Muslims and backward regions, on the basis of population. Women should constitute one-third of the total members elected from each political party (Article 85.8). If women are directly elected, each political party must ensure at least one-third of the members of the party are women. Article 85 of the Constitution of Nepal 2015 refers to 5 years’ term of the House of Representatives. Regarding representation under the PR in the PA, a closed list should include women, Dalits, indigenous nationalities, Khas Arya, Madheshi, Tharu, Muslims, backward regions, and minority communities, on the basis of population. Persons with disability (PWD) must be included in the PR list as well. Similar to the term of the House of Representatives, the Provincial Assembly also last for five years.

2.2 Electoral Constituencies and Voters

Formed on 20 July 2017, the Electoral Constituency Delimitation Commission (ECDC) submitted its final report to the government on 30 August with 165 electoral constituencies across the country (Table 1). Of the 165 constituencies for the election of the House of Representatives, Province 3 gets the most, i.e. 66. Province 6 and 7 get the least number of constituencies, 24 and 32 respectively. Similarly, Province 3 also get the highest number of constituencies for the election of the Provincial Assembly. Province 6, 7 and 4 receive 12, 16 and 18 constituencies respectively.

| Table 1: Electoral Constituencies and Voters in Nepal, 2017 | |||||

| Province Number | Population | Area (Sq. km) | Total Number of Districts | Number of PA Constituencies | Number of HoR Constituencies |

| 1 | 4,534,943 | 25,905 | 14 | 56 | 28 |

| 2 | 5,404,145 | 9,661 | 8 | 64 | 32 |

| 3 | 5,529,452 | 20,300 | 13 | 66 | 33 |

| 4 | 2,413,907 | 21,504 | 11 | 36 | 18 |

| 5 | 4,891,025 | 22,288 | 12 | 52 | 26 |

| 6 | 1,168,515 | 27,984 | 10 | 24 | 12 |

| 7 | 2,552,517 | 19,539 | 9 | 32 | 16 |

| Total | 26,494,504 | 147,181 | 77 | 330 | 165 |

| (Source: CBS, 2011; ECDC, 2017) | |||||

3. Election Administration

The Election Commission of Nepal (ECN) is a constitutional body mandated to conduct, supervise, direct and control the election of the President, Vice-President, and the members of the Federal Parliament, Provincial Assembly and Local Level (NLC, 2015). In addition to this, the ECN is also required to a hold referendum should matter of national importance related to the Constitution and the federal law emerge. Part 24 of the Constitution of Nepal integrates the composition and functions of the ECN. The Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) leads the ECN and is backed by four commissioners. The President of Nepal appoints the chief commissioner on the recommendation of the Constitutional Council (CC). Tenure of the CEC and other commissioners is 6 years from the date of appointment.

The Election Commission Act 2017 further describes the roles and responsibilities of the ECN (NLC, 2017). The ECN has over 11 major responsibilities such as advising the government to declare election date, asking for necessary security arrangement, monitoring election-related activities and campaigns, granting permission to election observers, stating ineligibility of the candidate, cancelling the election, conducting voter registration and awareness programmes, and other election-related policy issues. Preparing and enforcing election code of conduct and ceiling of election expenses to the candidates are other vital areas of jurisdiction to the ECN. For elections of the HoR and PA, the ECN mobilised staff in all 165 electoral constituencies across the country that included 77 district judges as the chief to administer elections.

Before the elections in 2017, 12,147,865 voters were registered in the second round of the voting of the Constituent Assembly in 2013. And so, the ECN had to update the list with a new registration drive throughout the country. Of 26 million population of Nepal (CBS, 2011), 15.4 million eligible Nepalese registered as voters for the election of the House of Representatives and the Provincial Assemblies (Table 2).

| Table 2: Population and Voters, 2017 | ||

| Province Number | Population | Total Voters |

| 1 | 4,534,943 | 2,993,774 |

| 2 | 5,404,145 | 2,767,375 |

| 3 | 5,529,452 | 3,074,384 |

| 4 | 2,413,907 | 1,568,924 |

| 5 | 4,891,025 | 2,740,864 |

| 6 | 1,168,515 | 846,941 |

| 7 | 2,552,517 | 1,435,673 |

| Total | 26,494,504 | 15,427,935 |

| (Source: CBS, 2011; ECN, 2017) | ||

While provinces 3 and 2 got the highest number of electoral constituencies, i.e. 33 and 32 respectively, provinces 3 and 1 get the highest number of the voters, 19.9 and 19.4 per cent of the total voters in Nepal (ECN, 2017b). Interestingly, Province 6 has the lowest percentage of voters, 5.5 per cent of all registered voters, but has the highest rate of voters registered to cast a vote in comparison to the provincial population, 72.58 per cent. Province 2, on the contrary, has the lowest percentage of registered voters in comparison to its population, i.e. 51.21 per cent.

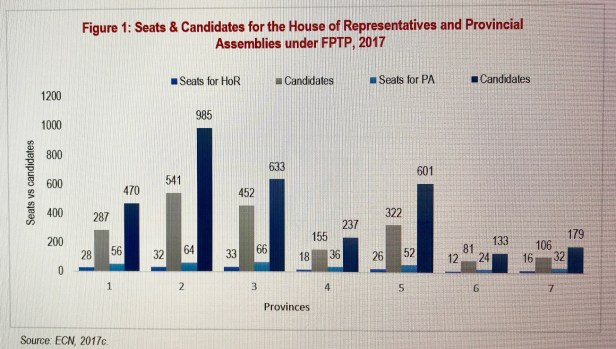

The ECN registered 5,182 candidates to contest in the elections of the House of Representatives and the Provincial Assembly, in all 7 provinces, under the First-Past-The-Post (FPTP). Of those 5,182, 1,944 referred the candidates to the HoR and 3,238 to the PA. 165 seats, under the FPTP, for the candidates are shared with 7 provinces where Province 3 secured the highest number of seats, 33 seats or 20 percent of the total. On the contrary, Province 6 gets just 7.3 percent, or 12 seats (Figure 1).

Looking at the seats and candidates’ ratio, Province 2 tops the list, with 541 candidates contested for 32 seats of the House of Representatives. A similar trend was also observed in the candidacy for the Provincial Assembly in Province 2 whereas 64 seats witnessed a competition among 985 candidates. This is more than 16 candidates per seat in the House of Representatives and 15 candidates per seat in the Provincial Assembly, in Province 2. Provinces 6 and 7 observed the least competition with less than 7 candidates per seat in the HoR and less than 6 candidates per seat in the PA.

Analysis of the voting trends, Province 1 entertained the highest number of voters per seat, 106,921 per seat in the HoR and 53,460 per seat in the PA (Figure 2). Province 5 witnessed second highest with 105,418 and 52,709 voters per seat in the HoR and PA respectively. Province 6 got the least number of voters (70,578 in the HoR and 35,289 in the PA) in the list of all seven provinces. Interestingly, Province 7, which stood at second-last position regarding the seats and candidates in the HoR and PA, has got more voters than Province 2 and 4.

4. Election Campaign and Finance

The history of elections and related campaigns in Nepal are comparatively peaceful with some incidents of violence and intimidation of candidates and the voters. Elections of the House of Representatives and the Provincial Assembly in 2017 also witnessed similar trends. Some incidents of violence across the country were observed in the forms of explosions, attack on candidates or party offices or campaign venues. Government’s effort to prevent such violent incidents could not be satisfactory. Despite that violence, political parties and independent candidates continued their election campaigns across the country. Various forms of the campaign were adopted by the political parties such as door-to-door, rallies, public meeting, talk shows, advertisements in different media outlets and on social media mainly on Facebook and Twitter. Differences between larger and smaller political parties could be observed regarding the use of media, some rallies, and social media handling. Larger political parties predominantly used national media outlets; television ads, radio jingles, and colourful advertisements in dailies, and they also influenced the campaign in social media. Smaller parties and independent candidates also used Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to reach to their constituencies in addition to a limited number of public gathering and door-to-door visits.

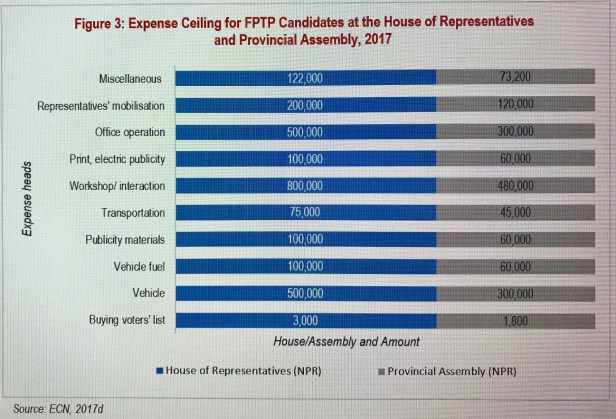

The ECN endorsed a maximum ceiling of the amount to prevent the influence of money in the elections. NPR 2.5 million was set as expenditure limit to each of the candidate contesting under the FPTP in the House of Representatives and NPR 1.5 million per candidate under the FPTP in the Provincial Assembly (Figure 3). Similarly, a ceiling was set at NPR 200,000 per candidate under the PR in the HoR and NPR 150,000 in the PA. However, the compliance of this expense ceiling remained ineffective. The ECN was criticised by the broader spectrum of society for their initiative to enforce the compliance strictly. Many warned against the excessive use of money to not just buy the influence and voters but also about the serious financial discrepancies in the future once these heavy-spending-candidates get into office (Rijal, ND).

5. Media

Media played a significant role during the elections of the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly. As usual, media roles could be grouped into two; informing voters about the electoral process and related issues, and highlighting the contesting parties, candidates and their agenda. In the absence of ECN’s inadequate efforts to reach, inform and educate ordinary citizens about the electoral processes, media outlets remained as the only source of information between electoral authorities and the voters.

In addition to Article 17 and 27 of the Constitution of Nepal 2015 which guarantees the right to freedom of opinion and expression and the liberty to information, Article 19 refers to the freedom of the press. However, the same Article also integrates a provision allowing the imposition of restriction on freedom of the press in certain conditions. In June 2016, the government issued Online Media Operation Directives 2073 (BS) to regulate the online media in the country (SAMSN, 2016). The Directives was reissued in March 2017 with some revisions as a response to addressing some of the concerns of media stakeholders. On the other hand, the government had issued the National Mass Communication Policy in June 2016 to develop fair and responsible mass communication. In addition to these legal and policy provisions to allow or restrict and develop media sectors in Nepal, professional development of journalists also faces other more pertinent challenges such as corporate-control, self-censorship, political influence/, encroachment of ethical conduct and professional standards and so on.

A total of 3,865 newspapers and magazines including 655 dailies, 30 bi-weeklies, 2,778 weeklies and 402 fortnightlies are registered in Nepal (PCN, 2017). In addition to the newspapers and magazines, local radio stations also play a significant role in highlighting grassroots issues across the country. 740 FM radios and 116 television companies are registered (MoIC, 2017) but about 505 radio stations and 16 television channels are in operation (PCN, 2017). Adding to the list, 753 online portals are registered with the Nepal Press Council. However, now all of these newspapers, magazines, radios and televisions are in regular operation.

The ECN- issued an Election Code of Conduct that regulated during the election, in addition to other stakeholders such as government, non-government and political parties. The Conduct required that media should remain impartial and factual, provide equal coverage to different political parties and candidates, and not to disseminate any fake news or information in favour of or against any candidate or political party, among others (ECN, 2017d). Any violation of the Conduct was subject to be punishable by the Election Commission Act, 2017. However, the limitation on the publication or broadcasting of political campaign or advertisements through media outlets was condemned by the media entrepreneurs claiming the provision of the Conduct was against ‘prevailing laws’ (HNS, 2017).

Despite the brawl between the ECN and media houses over press freedom, role and use of media during the election did not observe significant hassles. Many cases such as the injury due to IED explosion, detention of journalists, threats and attacks from contesting candidates were seen during the elections. The Federation of Nepalese Journalists (FNJ) and other journalists’ group condemned the incidents to curtail press freedom during elections.

Media, whether print or electronic or social media, provided a vibrant forum for issues, discussion, debate and advertisement of political parties and candidates. While bigger political parties, such as Nepali Congress and CPN-UML dominated the national and local media landscape, smaller parties shrunk to limited media coverage. The European Union Election Observation Mission to Nepal 2017 (EUEOM) monitored 13 media outlets with nation-wide reach found media landscape as generally balanced providing a proportionate distribution of airtime and space among the three bigger political parties, i.e. Nepali Congress, CPN- UML and the UCPN-Maoist (EUCOM, 2018). Press Council of Nepal reported 52 cases of the violation of Election Code of Conduct by 31 media outlets during the silence period. But no action was taken by the ECN regarding media outlets.

6. Participation of Women and Excluded Groups

The Constitution of Nepal 2015 requires inclusive representation of women and all social groups in the House of Representative as well as in the Provincial Assemblies across the country. As the electoral system in Nepal is a mixed one; FPTP and PR, representation of women, PWD and social groups are focused almost entirely at the seats under PR. The inclusive provisions are further elaborated in the electoral laws, rules and directives. In the House of Representative, a closed list under the PR system demands to share the seats with women and social groups. 31.2 percent of the seats under the PR is allocated to Khas Arya 28.7 percent to the indigenous nationalities, 15.3 percent to the Madheshi, 13.8 percent Dalits, 6.6 percent to Tharu, and 4.4 percent to the Muslims (ECN, 2017e). Furthermore, while PWD should be included in the list, women should share at least 50 percent of seats under each social group in addition to 4.3 percent of the candidates from backward areas.

In the Provincial Assembly, across the countries, the closed list under the PR system should consider the geographic balance and reflect the population of Khas Arya, indigenous nationalities, Madheshi, Dalits, Tharu, Muslim, backward region[1] and minorities[2] (ECN, 2017f). In addition, the PWD should also be included in the list. Whereas women should represent at least 50 percent of the total candidates under the PR from the respective political parties (ECNc, 2017g), women require to be at least 33 percent of the total members from each political party in the PA. A formula was integrated into the Rule of the Election of the Provincial Assembly Member, 2017 to share seats under the PR based on the population of major social groups in the concerned provinces (Table 3). However, an amendment in the Rule was later made to provide flexibility regarding meeting the quota for the social groups (ECN, 2017h).

| Table 3: Sharing of PR Seats in the Provincial Assembly Elections across Social Groups, 2017 | ||||||||

| SN | Candidates from |

Province and representation (in %) |

||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| 1 | Khas Arya | 27.84 | 4.89 | 37.09 | 37.24 | 28.84 | 62.2 | 60.02 |

| 2 | Indigenous nationalities | 46.79 | 6.61 | 53.17 | 42.37 | 19.58 | 13.63 | 3.61 |

| 3 | Madheshi Castes | 7.57 | 54.36 | 1.57 | 0.52 | 14.35 | 0.24 | 1.64 |

| 4 | Tharu | 4.15 | 5.27 | 1.66 | 1.72 | 15.18 | 0.5 | 17.21 |

| 5 | Dalits | 10.06 | 17.29 | 5.84 | 17.44 | 15.11 | 23.25 | 17.29 |

| 6 | Muslim | 3.59 | 11.58 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 6.94 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| 17.53 % from minorities and 0.44 % from backward areas/ party | 25.17 % from minorities and 2.11 % from backward areas/ party | 7.77 % from minorities and 1% from backward areas/ party | 6.02 % from minorities and 0.08% from backward areas/ party | 8.74 % from minorities and 1.17 % from backward areas/ party | 1.47 % from minorities and 32.4 % from backward areas/ party | 17.53 % from minorities and 0.44 % from backward areas/ party | ||

| (Source: ECN, 2017h) | ||||||||

7. Election Observation

Independent observation of the election not just increase the quality and impartiality of electoral process, it also supports the compliance with international and national instruments exist to ensure free and fair election. In addition to the Constitution of Nepal 2015 that protects the right to the freedom of expression, international norms such as the Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation (2005), and its accompanying Code of Conduct and the Declaration of Global Principles for Nonpartisan Election Observation and Monitoring by Citizen Organizations (2012) and Code of Conduct for Nonpartisan Citizen Election Observers and Monitors protect and promote the engagement of election observations.

The Election Commission of Nepal called for observation of the elections of the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly in 2017. The Election Observation Policy, 2017 and the Directive of the Election of the Members of the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly, 2017 sought observation of the elections based on the standards set by the ECN. (2017i). National and international organisations interested in observing the elections had to accredit with the ECN. A number of national and international organisations accredited and observed the elections in 2017. The European Union Election Observation Mission (EUCOM) and the Carter Center were the two international organisations whereas National Election Observation Committee (NEOC), General Election Observation Committee (GEOC), Election Observation Committee- Nepal (EOC-N), Sankalpa, Democracy Resource Center (DRC) in addition to COCAP were national organisations observed the elections. However, not all organisations observed across the country. While the ECN required to have national observation organisation to cover at least 100 polling stations representing Mountain, Hill and Tarai districts in all 7 provinces, national organisations’ reach varied due to the number of observers, availability of funding, and organisational strengths. Observations by national organisations also differed by their focus, e.g. electoral process or media monitoring or voter education or polling stations’ management.

8. Election Day

Depending on geography, population and administrative arrangements, voters cast their voted between 8 AM to 5 PM in most of the places. Representatives of the political parties were able to campaign freely, with some minor verbal confrontation in some areas, their presence was also observed during the polling day and in the centres. While the political activists remained peaceful and respected the Code of Conduct across the polling centres, cases of influencing the voters were also noted in some areas by offering food or drinks outside the centres. In some polling centres, observers noticed the presence of campaign materials within 300 meters diameter from the centre. The observers also experienced non-cooperation and hindrances from the polling centres’ staff which affected the smooth election observation. Despite the facility of permitting the PWDs to use the vehicle, the arrangement of vehicle pass distribution was not effective, and some PWDs were found to refrain from casting their votes due to the mobility issue.

With some flaws in the management of polling centres, accessibility issues of the PWDs, attempt to influence the voters near polling centres, obstruction in observation, and significantly ineffective voter education, the elections of the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly held successfully. Vote counting began on 7 December and completed within ten days; of the FPTP seats by 13 and of the PR seats by 17 December 2017. While the winners of the FPTP seats were announced by 13 December 2017, the announcement of the seats under the PR took longer than expected. The delay was also caused by the constitutional provision of having at least one-third of the total members from each political party present in the federal legislative must be women, and so the ECN waited until the election of the National Assembly held. Finally, the names of the members elected under PR system were announced on 14 February 2018. 15 political parties in addition to independent candidates succeeded to win the elections of the HoR and PA (ECN, 2017c). However, only five parties emerged as the national party due to the constitutional requirement of securing at least 3 per cent of the total votes to stand as the national party.

| Table 4: Elected Candidates from Political Parties/Independent, 2017 | |||||||

|

SN |

Political Party |

Provincial Assembly | House of Representatives |

Total |

% |

||

| FPTP | PR | FPTP | PR | ||||

| 1 | Nepal Communist Party – UML | 168 | 75 | 80 | 41 | 364 | 44.12 |

| 2 | Nepali Congress | 41 | 72 | 23 | 40 | 176 | 21.33 |

| 3 | Nepal Communist Party – Maoist Centre | 73 | 35 | 36 | 17 | 161 | 19.52 |

| 4 | Federal Socialist Forum Nepal (FSFN) | 24 | 13 | 10 | 6 | 53 | 6.42 |

| 5 | Rastriya Janata Party Nepal (RAJAPA) | 16 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 45 | 5.45 |

| 6 | Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0.48 | |

| 7 | Rastriya Jan Morcha (RJM) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0.61 |

| 8 | Naya Skakti Party Nepal (NSPN) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0.48 |

| 9 | Nepal Workers Peasants Party (NWPP) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0.36 |

| 10 | Bibeksheel Sajha Party (BSP) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.36 |

| 11 | Nepal Federal Socialist Party (NFSP) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.12 | |

| 12 | Federal Democratic National Forum (FDNF) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.12 |

| 13 | Rastriya Prajatantra Party (Democratic) (RPP-D) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.12 |

| 14 | Independent | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0.48 |

| Total | 330 | 220 | 165 | 110 | 825 | ||

| (Source: ECN, 2018) | |||||||

Winning over 44 per cent of the total seats, CPN-UML emerged as the largest party in the country (Table 4). Nepali Congress, the party winning the highest number of seats in the second Constituent Assembly Election in 2013, stood at the second position followed by UCPN- Maoist. Together, the CPN-UML and UCPN-Maoist (also formed an alliance known as Left Alliance), secured a clear majority with 64 per cent of the total seats- combining federal and provincial assemblies. Two Tarai/Madhesh based parties, Federal Socialist Forum Nepal (FSFN) and Rashtriya Janata Party Nepal (RAJAPA), obtained almost 12 per cent of the seats across the country. Remaining 26 seats, or 3.15 per cent of the total seats, are shared by eight political parties and independent winners.

At the House of Representatives, the Left Alliance dominates the federal politics by winning 174 out of 275 seats. Remaining 101 seats are shared by Nepali Congress (22.9%), two Madhesh-based parties (12%) and smaller parties (1.5%). Left Alliance also leads 6 out of 7 assemblies in the provinces where Madhesh-based parties get the just majority in Province 2 (see Annex 1 for detail results in the provinces).

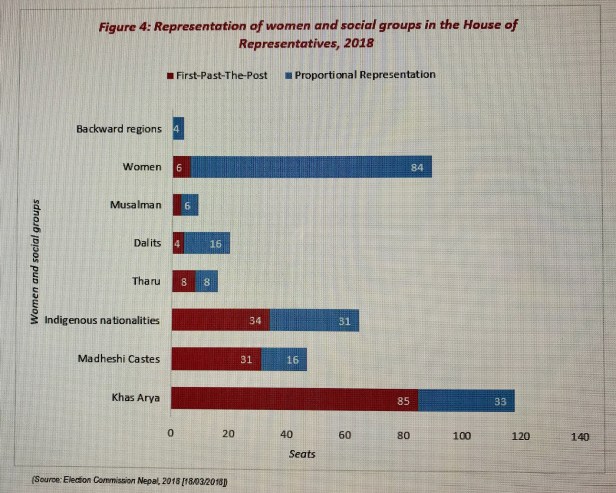

There are total 275 members in the House of Representatives; 110 elected from Proportional Representation (PR) and 165 members through First-Past-The-Post. Of the 165 members elected through FPTP, Indigenous nationalities represent 34 seats or 20.6 per cent whereas Madheshi Castes cover 18.8 per cent (Figure 4).

Tharu and Dalits live with 4.8 and 2.4 percent of the seats under FPTP, respectively. Muslims, having 4.4 percent of the population in Nepal, are limited to 1.8 percent whereas women just get 6 seats out of 165. Khas Arya leads both the FPTP and PR with 85 and 33 seats respectively. Madheshi Castes are having 14.5 percent of 16 seats out of 110 PR seats in the HoR. Indigenous nationalities get 28.2 percent, Tharu bags 7.3 percent and Dalits just 2.4 percent of the seats under the PR. Women, on the positive side, leads the PR seats with 76.4 percent whereas 4 seats are occupied by the PR candidates from Backward Regions. In total, Khas Arya leads the House of Representatives with 42.9 percent of the seats, FPTP and PR seats combined. The indigenous nationalities follow with 23.6 percent, Madheshi Castes with 17 percent, Dalits with 7.3 percent, Tharu with 5.8 percent and the Muslims get 3.3 percent of the total seats. Women get 32.1 percent of the seats whereas 4 seats out of 275 are with the representatives from Backward Regions.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite some weaknesses regarding compliance with the code of conduct, accessibility issue in some polling centres, and violent incidents, the ECN succeeded in holding peaceful and comparatively free elections of the HoR and PA. Only five political parties secured the status of ‘national party’. CPN-UML emerged as the largest party at the federal level, and the Left Alliance secured a dominant majority in 6 out of 7 provinces. Nepali Congress shrunk to 176 seats against 525 seats of the Left Alliance in HoR and all seven provincial assemblies. Two Madhesh-based parties, FSFN and RAJAPA, 12 per cent of seats across the country, with a just majority in Province 2.

In addition to the ECN and the government, the stakeholders have to collectively work to improve the quality and process of election management in Nepal. Electoral reforms, voter education, compliance with and enforcement of electoral laws and code of conduct are some of the significant areas of improvement.

The elections of the HoR and PA instil hopes and fears of the people and the political parties. Hopes that the transition under which Nepal has been struggling to end for over two decades will be over after the elections for new federal structures. Fears whether the political parties are able not just to hold periodic elections as scheduled but are also committed to meet people’s aspirations in a changed political setting, as promised during election campaigns. Changing patterns of electoral campaigns, the manifesto of political parties and increasing public and media scrutiny over entire electoral process and results reflect that Nepal is rapidly transforming and political masters must shift from behaving as an ‘elected ruler’ to a reliable public steward who delivers.

[1] The government declared 57 areas, rural and town municipalities, as backward areas.

[2] 98 caste/ethnicities, representing less than 0.5 percent of the national population each, were enlisted as minorities.

References

CBS, 2011. Housing and Population Census 2011 Report. Kathmandu.

Department of Printing (DOP), 2017. Provincial Assembly Election Law 2017. Kathmandu.

ECDC, 2017. Report of the Electoral Constituencies Delimitation Commission. Kathmandu.

ECN, 2017a. House of Representatives Election Law 2017. Kathmandu.

ECN, 2017b. Elections of the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly 2017, Description of Districts and Voter Number. Kathmandu.

ECN, 2017c. Quantitative description of election candidates from political parties and independent. Kathmandu.

ECN, 2017d. Election Code of Conduct (with amendment). Kathmandu.

ECN, 2017e. HOR Member Proportional Election Directives (inclusive of All Amendments). Kathmandu.

ECN, 2017f. Province Assembly Member Proportional Election Directives (inclusive of all Amendments). Kathmandu.

ECN, 2017g. Rule of the Election of the Provincial Assembly Member. Kathmandu.

ECN, 2017h. The First Amendment in the Rule of the Election of the Provincial Assembly Member. Kathmandu

ECN, 2017i. Election Observation Policy, 2017. Kathmandu.

ECN, 2018. Party-wise Elected Summary. Kathmandu

EUCOM, 2018. House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly Elections 2017, Final Report. Kathmandu.

Ghimire, B., 2017. Constitution amendment bill fails in Parliament. The Kathmandu Post, assessed on 15/04/2018 at http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2017-08-22/constitution-amendment-bill-fails-in-parliament.html

Giri, S., 2017. CDC submits its report with 165 electoral constituencies. The Kathmandu Post, assessed on 15/04/2018 at http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2017-08-31/cdc-submits-its-report-with-165-electoral-constituencies.html

Haviland, C., 2015. Why is Nepal’s new constitution controversial? BBC, assessed on 15/04/2018 at http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-34280015

HNS, 2017. NMS concerned about Election Commission’s warning to media. The Hiamalayan Times, assessed on 20/04/2018 at https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/nepal-media-society-concerned-about-election-commissions-warning-to-media/

ICG, 2016. Nepal’s Divisive New Constitution: An Existential Crisis, Asia Report N 276. Brussels.

Koirala, K. P., 2016. Nepal makes first amendment of its constitution four months after promulgation. The Himalayan Times, assessed on 15/04/2018 at https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/breaking-nepal-makes-first-amendment-of-its-constitution/

Ministry of Information and Communications (MoIC), 2017. List of Licensed FM Radios, Kathmandu.

MoIC, 2017. List of Licensed FM Radios, Kathmandu.

NLC, 2015. The Constitution of Nepal 2015, Kathmandu.

NLC, 2017. Election Commission Act 2017, Kathmandu.

Press Council Nepal (PCN), 2017. Annual Progress Report 2074 BS, Kathmandu.

Rijal, M., ND. Escalating Election Expenses. The Rising Nepal, assessed on 20/04/2018 at http://therisingnepal.org.np/news/20494

RSS, 2016. UML-aligned organisation wins trade union poll. The Himalayan Times, assessed on 02 June 2016 at https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/uml-organisation-wins-trade-union-poll/

SAMSN, 2016. Press Statement released on 28/03/2017 and available at https://samsn.ifj.org/nepal-reintroduces-restrictive-online-media-directives/

South Asia Media Solidarity Network (SAMSN), 2016. Press Statement released on 28/03/2017 and available at https://samsn.ifj.org/nepal-reintroduces-restrictive-online-media-directives/