Introduction

Nepal is in the process of transitioning to a system of federal governance. As the restructuring of state unfolds, the country is still struggling to have a clear roadmap of the journey to federal governance, or even clarity on what the final destination will be. This prolonged transition, led by a narrow circle of decision makers, raises fears and doubts about both the process and its likely outcomes. People in all walks of public life are affected, as are development projects. This assessment aims at reviewing the ongoing federalisation process in Nepal and identify the probable impact of federalism on the school safety projects.

The assessment is based on a literature review. Literature from government ministries and departments, and experts and practitioners involved in federalism, state restructuring, the education sector, foreign assistance and social development, served as the foundation of this assessment. However, the assessment has limitations. The information or documents collected may have missing details, updated versions or counter-arguments. Key findings and recommendations in this assessment are based on the literature reviewed and can only be as accurate as the source documents from which they are drawn. Since the federalisation process is ongoing and many actors are simultaneously engaged in producing new policy, law and procedures, there is a need to review and update this report on a regular basis.

The paper aims at informing the programmes and projects with an overall objective of promoting resilience in public schools in vulnerable communities in Nepal. The assessment can particularly help in reviewing its established strategies, approaches and implementation plan and tailoring them to the changing context to minimise adverse effects as well as transform the challenges of Nepal’s transition to federalism into opportunities. The assessment is divided into three parts; school education in Nepal, education management in federal system, impact of federalism on school safety[1], and conclusions.

Discussion

The demands and developments towards restructuring the territories and regions of Nepal in a bid to better govern the country, leading to the current transition to a federal system, did not spring up suddenly or spontaneously, but have been in gradual development for decades. Today’s Nepal comprises multiple principalities and territories brought together under a unification process which began during the mid of 17th century. During the Rana regime, Nepal was divided into 20 Hill, 9 Tarai and 3 Inner Tarai districts. In 1961, Nepal was restructured into 75 districts and 14 zones, and later in 1972, the country was divided into four development regions. In 1982, the Far-Western Region was divided into two – Mid-Western and Far-Western. However, the first demands for federalism emerged in the early 1950s when the Nepal Terai Congress, established in 1951, stated the objective of establishing an autonomous Terai region. The restoration of democracy in 1990 encouraged a sense of awareness of systems of governance among civilians and excluded groups, particularly indigenous nationalities (IN) and Madheshis, in southern Nepal.

The Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN) was established in 1991 as an umbrella organisation for IN in Nepal with the aim of furthering the cause of INs, including claims to autonomy and the right to self-determination. In its 1991 manifesto, the Nepal Sadbhawana Party (NSP) highlighted the need to declare other autonomous regions, in addition to the Terai, in the hills and mountains. In February 1996, the United People’s Front, Nepal (UPFN) submitted a 40-point list of demands to the government that included restructuring of the state and transforming governance to better connect local and excluded regions and communities with the state. During the Armed Conflict (1996-2006), the Maoists declared nine autonomous regions. In March 2007, the First Amendment in the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2007, affirmed federal governance as a replacement for the centralised and unitary structure of the country, and declared an end to discrimination based on caste, class, language, religion or region.

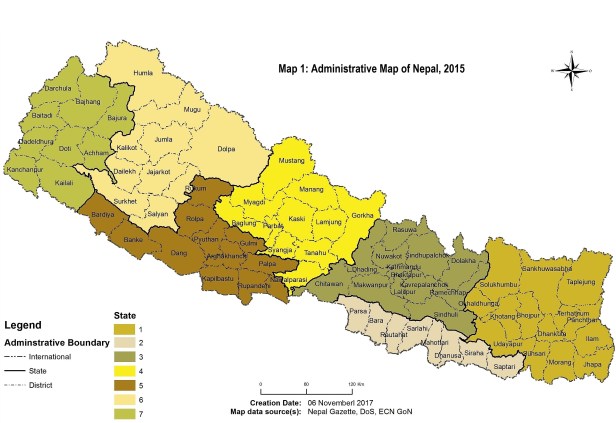

(Source: UN, 2018)

With some changes in the interim period regarding declaration of municipalities and Village Development Committees (VDCs), over 3,157 VDCs and 217 municipalities existed in Nepal in late 2015. The 7th statute of the country, the Constitution of Nepal (2015), has restructured the country into 7 provinces and 753 local levels. Local levels include rural and urban municipalities in addition to districts. Nepal now comprises 6 metropolitan areas, 11 sub-metropolitan areas, 276 urban municipalities and 460 rural municipalities, in addition to 77 districts (Map 1).

1. School education in Nepal

1.1 Overview of schools

The existing federal school system in Nepal includes both primary education (to grade 8), and secondary education (grade 9-12). There are 35,601 schools in Nepal, of these, 27,883 (78.3 percent) are community schools, 6,566 are organisational (or private) schools, and 1,152 (3.2 percent) are religious schools. Of those 35,601, 35,211 run basic/primary level grades (1-5), 15,632 run grades 6-8, and 35,393 run grades 7-8 (Table 1).

| Table 1: List of schools in Provinces | |||||||

| Province | Total school unit | Grade-wise operational schools | |||||

| Basic/Primary | Secondary | ||||||

| (1-5) | (6-8) | (1-8) | (9-10) | (11-12) | (9-12) | ||

| 1 | 6,721 | 6,673 | 2,897 | 6,699 | 1,598 | 676 | 1,643 |

| 2 | 3853 | 3819 | 1348 | 3845 | 709 | 401 | 740 |

| 3 | 7388 | 7240 | 3884 | 7266 | 2590 | 978 | 2727 |

| 4 | 4607 | 4544 | 2054 | 4570 | 1341 | 561 | 1361 |

| 5 | 5764 | 5728 | 2476 | 5754 | 1433 | 532 | 1463 |

| 6 | 3199 | 3161 | 1182 | 3187 | 574 | 230 | 574 |

| 7 | 4069 | 4046 | 1791 | 4072 | 926 | 403 | 939 |

| Total | 35,601 | 35,211 | 15,632 | 35,393 | 9,171 | 3,781 | 9,447 |

| (Source: MoF, 2018a; MoEST, 2018) | |||||||

At the secondary level, 9,171 schools operate grades 9-10, 3,781 run grades 11-12, and 9,447 schools run grades 9-12. Province-wise, Province 3 has the most schools with 7,388 (20.8 percent), Provinces 1 and 5 follow with 18.9 and 16.2 percent of the total schools in the country and Provinces 6 and 2 have the fewest with 9 percent and 10.8 percent, respectively.

| Table 2: School, Student &Teacher Ratio in Provinces | ||||||||

| Province | School-Student Ratio | Teacher- Student Ratio | ||||||

| Basic | Secondary | Basic | Secondary | |||||

| (1-5) | (6-8) | (9-10) | (11-12) | (1-5) | (6-8) | (9-10) | (11-12) | |

| 1 | 88 | 108 | 100 | 163 | 25 | 50 | 35 | 83 |

| 2 | 210 | 190 | 165 | 189 | 59 | 92 | 53 | 106 |

| 3 | 98 | 102 | 80 | 114 | 24 | 48 | 32 | 63 |

| 4 | 73 | 95 | 82 | 136 | 18 | 42 | 29 | 60 |

| 5 | 127 | 135 | 112 | 180 | 38 | 71 | 44 | 81 |

| 6 | 107 | 130 | 123 | 135 | 40 | 80 | 55 | 51 |

| 7 | 116 | 122 | 126 | 206 | 40 | 71 | 53 | 72 |

| Nepal | 113 | 119 | 103 | 154 | 33 | 60 | 40 | 73 |

| (Source: MoF, 2018a; MoEST, 2018) | ||||||||

Variations in schools-to-student and the teacher-to-student ratios can be observed across Nepal. For example, at grade 1-5 level, the ratio of schools-to-student is 1:113, 1:119 at grade 6-8, 1:103 at grade 9-10 and 1:154 at grade 11-12 as reported for the academic year 2017 (Table 2). Province-wise, Province 2 has the highest disparity in schools-to-student and teacher-to-student ratios at all grades except in grade 11-12 where Province 7 tops the list. Provinces 4, 3 and 1 show lower gaps in both ratios. While Province 6 has the fewest schools, it performs better than Province 2 in terms of the ratio measurements.

1.2 Investment in education sector

Although the new Constitution declares education as a fundamental right, the allocation of budget to the sector does not necessarily reflect this. Although the current FY budget increases the share for education, it is still at a lower level than in FY 2016/17 (FCGO, 2017; MoF, 2017a; 2018c). The highest spending on education as a proportion of the national budget was in FY 2011/12, with 18.3 per cent of the total expenditure, declining to a nadir of 5.09 in 16/17 and rebounding slightly to 10.20 per cent of the total national expenditures in FY 2018. While the education sector’s share of the national budget has declined, its portion of national GDP has gone up slightly. For example, the education budget had 4.19 per cent share of the national GDP in FY 2011/12 but increased to 4.85 per cent in FY 2016/17 (MoF, 2018a).

In addition to government funding, the education sector is also one of the favourite baskets targets for foreign assistance. In FY 2016/17, the education sector received the largest chunk of ODA disbursement. However, the trends of sector-wise disbursement of foreign aid have been changeable in the recent past. For example, although the education sector received US$ 127.24 million in FY 2016/17 and emerged as a top priority for donors (in the same FY), the amount is less than in previous years. It had received more funds in the past (MoF, 2017a). In FY 2017/18, US$ 162.9 million was disbursed in the education sector (MoF, 2018c).

The School Sector Development Plan (SSDP; FY 2016/17-FY 2022/23) is the long-term strategic plan of the federal government aimed at increasing participation of all children in quality school education by focusing on strategic interventions and new reform initiatives, to improve the equitable access, quality, efficiency, governance, management and resilience of the education system. The MoESTE is the executing agency, and the Department of Education (DOE) is the implementing agency of the SSDP, into which multiple donors are providing funding through a Joint Financing Arrangement (JFA). Other development partners and I/NGOs are also members of Local Education Development Partner Groups (LEDPG) who support in the education sector. A Programme Implementation Manual (PIM) is to be shared with all 753 local governments by to ensure smooth management of the SSDP at the local level (MoESTE, 2018). Of the total education sector budget ceiling of NPR 127 billion (US$1,212 million), 76.6 per cent (US$928.2 million) is allocated to the SSDP (in FY 2018/19).

Comparing the budgets of education sub-sectors, primary education has remained the top priority for the last 7 years. Primary education is followed by secondary education which gets over 10 per cent of the budget allocated to the education sector in Nepal (Table 3). However, both primary and secondary education have experienced significant changes in budget allocation in recent fiscal years. Secondary education has seen the largest decrease in budget, by 6.28 per cent in the last 7 years. In contrast, the budget for primary education has risen by 4.64 per cent in the same period. If primary and secondary education sectors are combined, their share of the education sector was 85.55 per cent in 2010/11, decreasing to 83.91 per cent in 2016/17. It is essential to increase investment now since education up to secondary level is promised to be free in the new constitution.

| Table 3: Budget Allocation to Education Sub-sectors (FY 2014/15- 2016/17) (%) | ||||||||

| SN | Sub-sector | 2010/11 | 2011/12 | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 |

| 1 | Primary education | 68.47 | 68.86 | 67.62 | 68.57 | 65.58 | 68.47 | 73.11 |

| 2 | Secondary education | 17.08 | 16.69 | 18.24 | 18.2 | 20.67 | 17.92 | 10.8 |

| 3 | TEVT | 2.36 | 3.62 | 2.06 | 2.91 | 3.78 | 3.31 | 2.81 |

| 4 | Tertiary education | 10.04 | 9.02 | 10.17 | 8.33 | 7.93 | 8.19 | 8.55 |

| 5 | Education management & administration | 1.99 | 1.77 | 1.88 | 1.96 | 2.01 | 2.08 | 4.7 |

| 6 | Others | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| (Source: MoEST, 2017) | ||||||||

1.3 Challenges of school education in Nepal

Despite good investment and attention to education, this important social sector suffers from various political, administrative and quality issues. Political alignment of teachers and school management committee (SMC) members is probably the most challenging issue the education sector is facing to ensure quality and competitiveness. Mobilization of teachers, staff and SMC members can also be observed during major political campaigns and elections. Increasing numbers of teachers, not just who undergo the formal examination of service but also those appointed on temporary and relief quotas, share a growing portion of the education sector budget. For teachers, political alignment can be helpful to circumvent strict compliance with attendance at schools, respect to the timely implementation of the teaching calendar, adherence to school codes of conduct, and support in improving the teaching and learning environment of the school. For SMC members, political affiliation can mean better access to government funds, increased bargaining capacity with the education authority for more teachers and staff, access to external grants and assistance, respect within their own political party, and manipulation of resources at the school.

Administratively, the power hierarchy at the schools directly affects the formation/election, operation/management and role of SMCs in the school environment. For example, SMCs are mandated to ensure the quality of the education and learning environment, as well as checking the performance of staff and teachers. In many areas, teachers and staff tend to be more (educationally) qualified than SMC members, putting the SMC’s in a fragile position to monitor the performance of staff and teachers. Roles and responsibilities of the SMC are well defined. So too the roles and responsibilities of head/teachers and staff. While SMCs should include representation from parents/guardians of the school children, some SMCs include instead non-parent/guardian community members who are affluent and/or politically connected. Clashes between SMC members and head/teachers, can escalate if either or both sides are backed by politicians. This seriously jeopardizes the quality of participation in preparing a school improvement plan (SIP), implementation and compliance with applicable standards and regulations. Without proper standardization of and conformity to the SIP and other school affairs, schools suffer from falling pupil numbers, and reduced budget for improving infrastructure and other facilities.

The quality of public/community schools is another area that benefits private boarding schools but not the public ones. With some exceptions regarding well-performing community schools, average public schools suffer from numerous quality issues. The irregularity of teachers’ own attendance, lack of child/student-friendly teaching approaches, lack of basic infrastructure, delay or unavailability of books and other important stationery, the manipulation of scholarships and other benefits to children from excluded and poor backgrounds, non-compliance with the academic calendar, inadequate testing and grading systems, lack of incentives for innovation and quality, corruption in terms of teacher/staff appointments and manipulation of school funds are some of the standard challenges public schools face around the country. While private schools claim to provide better education and learning opportunities, poor working conditions for teachers, financial exploitation of parents and unwarranted needs for dress code, and sub-standard curricula may help students achieve better marks in the short term, but do not necessarily succeed in achieving quality education and life-long learning.

1.4 Natural disaster and school education

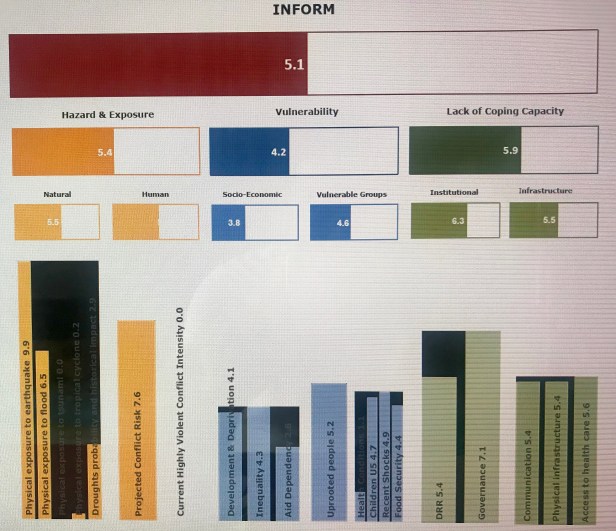

Nepal is exposed to a number of natural hazards due to its unique geological and hydro-meteorological location. Nepal scores 5.1 on the INFORM (Index for Risk Management) scale of risk to humanitarian crises. Nepal gets a Hazard, and Exposure risk of 5.4/10 (1 being the lowest and 10 being the highest), a Vulnerability risk of 4.2 and a Lack of Coping Capacity risk of 5.9 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: INFORM Country Risk Profile for Nepal, 2018

(Source: INFORM, 2018)

Inadequate attention to proper land use, rapid urbanization, disaster preparedness, per capita income, harmonization of disaster in the mainstream of public policy, accountability and effectiveness of public response mechanisms, and strengthening preparedness and response capacity at the local level, increases the vulnerability of the country to disasters and their impacts. Due to the lack of preparedness and availability of sufficient resources to respond, even a minor disaster can lead to severe damages and casualties. Avalanches, cold and heat waves, droughts, fires, floods, disaster-induced epidemics, landslides, and earthquakes are just some of the common disasters which occur regularly causing risk to human lives and basic public infrastructure. The devastating earthquakes of 2015 and the floods and landslides in 2017 have reiterated the need for a robust policy direction towards adopting and implementing short and long-term disaster preparedness and response policy plans. The Post-Disaster Need Assessment (PDNA), 2015, is a concrete step towards addressing these policy gaps at the national level. The PDNA outlines short-term priorities: the reconstruction of damaged DRR assets; improvements in preparedness, response, relief and logistics management; adoption of measures to improve multi-hazard risk monitoring, vulnerability assessments and awareness, as well as long-term priorities: improvement in legal and institutional arrangements; improve policy and institutional conditions to climate change adaptation and DRR; and mainstream DRR into development and social sectors such health and education; (NPC, 2015). However, the PDNA, as well as other disaster-related policy instruments, needs to be contextualized in federal arrangements.

Some initiatives have taken place to increase disaster preparedness in schools, for example the integration of DRR into educational materials and school curricula, planning and support for disaster preparedness plans and programs, endorsement of a standard design of schools and classrooms, programs to strengthen/ retrofit weak school buildings, and integration of school-related DRR priorities in the recently endorsed National Disaster Risk Reduction Policy, 2018 (GoN, 2018a; MoHA, 2016; PAC, 2017). The National Disaster Risk Reduction Policy, 2018, highlights priority areas and is set out further in the Disaster Risk Reduction National Strategic Action Plan (2018-2030). The Plan attempts to review the implementation of past policy directions and strategies and how these can be contextualized in a new federal setting to have federal, provincial and local level governments work in a synchronized manner to prepare and respond to disasters (GoN, 2018b). The Policy and Action Plan both directly contribute to the implementation of DRR and resilience in public schools and also to creating and supporting a conducive environment for safer school principles.

The school related DRR principles are guided by three overlapping areas of focus: safe school facilities, school disaster management, and disaster prevention education. In Nepal, the principles of safer schools are contextualized in the Comprehensive School Safety Framework and have been adopted by organizations working across the education sector. The Framework seeks to ensure that children and the wider school community (staff, teachers and SMC members) create an enabling environment to meet the minimum safety standards to protect children from disasters (MoE, 2017). The Framework has three inter-related components: safer learning facilities, school disaster management, and risk reduction and resilience education. Another policy, Nepal Safe School Policy, is awaiting approval from the government and is expected to provide an overarching policy framework to implement a master plan (Comprehensive School Safer Master Plan, Nepal 2017) and minimum packages (Comprehensive School Safety Minimum Package; Volume 1 & 2) developed by the federal education authority, Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST).

2. Education management in federal system

Education is considered an essential part of constitutional power-sharing between federal units. All three levels of governance; federal, provincial and local level have shared responsibility to ensure education for their constituencies. At the national level, the federal government is responsible for central level universities and libraries in addition to formulating policy, law, standards and regulations related to central level educational institutions and national education-related affairs. At the provincial level, the provincial government is leading the task of policy and law formulation pertaining to provincial level universities and higher education. The local level government primarily looks after basic and secondary level education (Table 4). While federal and provincial governments share the obligation of scientific research, technology and human resource development, all three units of the federal system work together to ensure that education is a priority for all.

Table 4: Education Related Constitutional Powers to Federal Units in Nepal, 2015

| SN | Federal Government | Provincial Government | Local Level Government |

| A. Exclusive Powers | Central universities, central level academies, universities standards and regulation, central libraries (Schedule 5: 15) | State universities, higher education, libraries, museums (Schedule 6: 8) | Basic and secondary education (Schedule 8: 8) |

| B. Concurrent Powers | Scientific research, science and technology and human resources development. (Schedule 7:22) | ||

| Education, health and newspapers (Schedule 9: 2) | |||

| (Source: Schedule 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9, The Constitution of Nepal, 2015) | |||

Under Article 11.2.H, the Local Government Operations Act 2017 (LGOA) elaborates the role of the local level government to plan, deliver and manage basic and secondary level education. Some of the key roles of local level governments are as follows:

- Law, policy, standard, plan, implementation, and regulation in relation to all types of education and learning centres (up to secondary level);

- Distribution of curriculum, teaching and learning materials;

- Adjustment of employees and teachers at community school;

- Mapping, adjustment and regulation of schools;

- Construction, maintenance, operation and management of infrastructure at community schools;

- Student learning, encouragement and scholarships;

- Protection and standardisation of educational knowledge, skills and technology at the local level;

- Rural and urban municipality level education committee formation and management;

- School management committee (SMC) formation and management;

- Grant and budget management; financial discipline, monitoring and regulation of community schools; and

- Learning, training, and capacity building.

Federalising the education sector involves multiple government actors and agencies (and broader stakeholders including donors, political parties, civil society, education-related professionals, parents and students) to systemically plan and execute policy, law and actions at federal, provincial and local levels. To be more precise, the following table (5) illustrates some of the significant efforts to federate the education sector in Nepal:

Table 5: Immediate & Short-Term Priorities to Federate Education Sector in Nepal

| Level | What? | Entails? | Responsible? | |

| Federal | Formulation of law, policy, standards and regulations in relation to national universities, central libraries, and higher education. | E.g. Federal Education Act; educational structures to suit federal context; teachers and staff mapping, realignment, mobilisation and management; national vison/plan for educational sector reform and development; foreign assistance regulation; standardisation of provincial educational policies, core curriculum, infrastructure and quality/standard of grade/ qualification; transfer, management and scrutiny of grants, loan and technical assistance. | Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST)

Ministry of Finance (MoF)

|

|

| Provincial | Formulation of provincial law, policy, standards and regulations in relation to education in the province. | E.g. Provincial Education Act; educational structures to suit provincial context and needs; teachers and staff mapping, realignment, mobilisation and management; provincial vison/plan for educational sector reform and development; standardisation of local level educational policies, curriculum, infrastructure and standard of qualification; transfer, management and scrutiny of grants, loan and technical assistance. | Ministry of Economic Affairs and Planning (MoEAP)

Ministry of Social Development (MoSD) |

|

| Local | In line with Local Government Operations Act 2017 (LGOA), formulate policy, law, standards, plan, programmes/ projects, implement and review in relation to basic and secondary level education. |

|

District Coordination Committee (DCC)

Education Development and Coordination Unit/DAO

Nagar/ Gaun Palika (Urban/ Rural Municipality)

Ward Office |

|

| (Source: FIARCC/OPMCM, 2017;GON, 2017; MoE, 2017) | ||||

3. Impacts of federalism on school education

Social sectors, such as health and education, see decreasing attention from decision makers to expand services and improve quality. On the flip side, health and education emerge as a high-return-on-investment sector for private investors turning essential public services into for-profit enterprises. But, the state is pledged to deliver primary and secondary level education, as required by the new Constitution, as a fundamental right to its citizens. The education sector also attracts high levels of foreign assistance and so a smooth transitioning of the education sector can be anticipated. However, domination of federal politics and bureaucrats will not be indisputable at all provincial and local levels.

Some problems may present existential dangers to the project, while others may affect implementation without posing any serious risk. To elaborate the risks further, five obvious impacts of federalism on the school safety interventions are highlighted in the next paragraphs. Similarly, to deal with the challenges or minimise the negative impacts of federalisation process on the intervention, it is recommended to proactively engage with relevant stakeholders to be able to capitalise the transition. Clear communication, frequent interaction, transparent project management, and pro-active engagement on policy/ law/ budget/ programme formulation, design and implementation do not just minimise the risk of unwanted influence or manipulation during the transition, they also increase the opportunity to influence agendas and partnerships, and sustain the outputs the intervention create. Strategies are also discussed to not just minimise the negative impact of federalisation, instead transform the transition into an opportunity to lead and create sustainable change for school safety in Nepal.

3.1 Clash over jurisdiction

The Constitution of Nepal, 2015, clearly divides constitutional powers between the three units of the federal system. Primary and secondary education is the exclusive power of the local level government. In practice, however, the federal government takes full control over federalising the education sector, including primary and secondary level school education. At the same time, provincial governments also seek a role in regulating and managing policy, directives and standards of the schooling system in their jurisdiction. At the local levels, rural and urban municipalities challenge the legal ground for having district level authorities (e.g. District Coordination Committee, or DCC, and District Administration Office, or the DAO) regulating the education system in their jurisdiction.

In addition to the federal, provincial and local level governments, various structures within these governments also seek their roles. For example, while the federal Ministry of Finance (MoF) decides the budget allocation for the education sector, the province level Ministry of Economic Affairs and Planning (MoEAP) is responsible for allocation and disbursement of grants to local levels. Similarly, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST), at the federal level, is responsible for educational policy, law and the standardisation of curriculum and certification, while the Ministry of Social Development (MoSD) at the province level is responsible for managing social sectors (e.g. health and education) within the respective province. Although the constitution allows rural and urban municipalities to exercise legislative and executive powers (demanding them to prepare and endorse laws and policies that matter to thme, such as the Municipal Education Act and Disaster Risk Reduction Policy), having the DAO coordinating district-level education committees contravenes their constitutional jurisdiction. While the DAO functions under the federal Ministry of Home Affairs (MoHA), which is also a central ministry for coordinating disaster response, local levels (including DCCs) are coordinated by the federal Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration (MoFAGA). To the worse, a clash over jurisdiction between municipal and ward councils affects a shared vision for development at the municipal level.

Impact on school safety intervention:

The clash over jurisdiction has a direct impact on the work of school safety projects. For example, if not harmonised and standardised between federal units, uniformity of design and estimates of retrofitting/construction (school facilities) can’t be maintained. Likewise, the realisation of disaster management and disaster prevention education depends on the commitment and action of government stakeholders. Conflict or confusion of jurisdiction between them can cause a delay in having a shared understanding of the agreed plan, the share of resources, and support or leadership in timely implementation. The conflict between municipality and district level authorities over mapping, realignment and recruitment of teachers, priority setting in sectors such as education and DRR, and oversight over SMCs can also influence the quality of the engagement with stakeholders and the implementation of priorities. Disputes or ambiguity of jurisdiction between and among federal, provincial and local level governments and their units will have a regular impact on the project.

Mitigation strategy:

Track the federalisation process with a focus on legal and policy jurisdictions of education and disaster risk reduction related federal, provincial and local level authorities. These should include, but not limited to, formulation and implementation of federal, provincial and local level education and DRR related laws, policies, institutions, and organisational communications and behaviours. As the federalisation process lasts beyond 2018, conduct periodic assessments to identify the trends and impact on the project outcomes with a focus on working provinces and municipalities. Furthermore, devise appropriate communication message and tools to inform the relevant stakeholders as required, but more frequently during 2018-2019. The message should highlight the objectives and approaches of education intervention/s to avoid unnecessary attention and brawl over the resources. Clear communication should be accompanied by regular coordination with the relevant stakeholders to build and sustain rapport with an aim to get their buy-in in project management.

3.2 Resource versus responsibilities

Essential services such as health, education and disaster management fall under local level governments. While local levels play a primary role in collecting revenues and royalties, 70 per cent of that income goes to federal funds and 15 per cent to the provincial government, and only 15 per cent goes back to local levels. Fascinatingly, a very limited number of local levels are able to generate more revenue or royalty than their recurrent expenditure continuing their dependency on national government and external funds to survive. This positions local levels at odds to deliver essential services. While the federal government retains a significant portion of revenues and royalties, it can quickly shift responsibility to local levels as an accountable body to meet people’s aspirations. Similarly, inadequate financial resources lead to sub-standard services and products at the local level. Limited access to financial resources also increases tension between local level representatives and officials over allocation, distribution and benefits to their constituencies. Having the provincial government play a coordination role between federal and local levels is more complicated than it appears. Provinces have both similar and unique characteristics regarding development, demography, geographic and economic perspectives. While better performing provinces expect to advance more and make their province an example, other not so well performing provinces need more time and resources to catch up with the national average. The current practice of budget allocation to provincial and local levels can help them survive, but they need more autonomy, resources and support from the federal government to thrive.

Impact on school safety intervention:

Financial resource constraints at counterpart government agencies will directly impact the intervention, especially the outcomes, in two ways. First, limited budget or resources at municipalities will tend to prioritise recurrent expenditures, not capital financing. As a result, long-term commitment and multi-year projects will be replaced with smaller, short-term projects shared between the municipal and ward council members. Second, investment and responsibility for ensuring improved learning and education environment as well as the integration of DRR in SIP, and school level DRR in municipal and provincial level policy plans, are likely to be affected due to budgetary limitations. The federal government can provide additional funds and mandates to provincial and local levels if resources are not enough to meet the needs. However, the vertical flow of additional funds will very much depend on the individual relationship between the leaders of respective units rather than an established norm. This can cause fluctuating financial resource availability at the partner municipalities resulting into varying dependency on project/s to meet the school safety outcomes. Funds received through political connection, and not a process-led distribution of power and resources, seeks to favour the narrow political and social circle while prioritising local level development, including quality of education and disaster resilience. This directly affects the quality of project/s integration in local planning and development priorities. The project will suffer more in the initial period since roles, responsibilities and resource allocation patterns are likely to be clarified in the first year and fully established in the consecutive years. Retrofitting component is expected to remain less affected in this trend whereas the other two outputs face different challenges throughout the project period due to resource-sharing and prioritisation needed from partner municipalities.

Mitigation strategy:

Monitor the resource flow and allocation in the partner provinces and municipalities, even if the intervention does not seek monetary contribution from partner schools or municipalities. However, the qualitative achievements of project outcomes require the full cooperation of partner municipalities and schools to integrate school safety components in SIP and municipal DRR policy and programmes. The degree of collaboration will be directly impacted by the resources available at the partner schools and municipalities. So, it is recommended to monitor the internal and external fund flows in the schools and municipalities as well as the allocation of funds to support school safety. This can help the project/s to reevaluate the investment needed in each of the partner municipality and school to fulfill project objectives rather than a standard one.

3.3 Capacity to deliver

Federal, provincial and local level governments all lack the skills and experience to deliver in the new federal setting. The move against international experts to help devise effective public policy, discourages external offers to fill the capacity gap as well as leaving a vacuum for local capacity building to drive a better governing system. Having the existing bureaucrats and their loyal experts plan and implement the transition is full of risks of replicating mistakes of the past. While the people and excluded regions expect more than just a governing structure to collect tax and impose regulations, a revised version of decentralisation controlled by the centre will not deliver better services in federalism.

The federal authority restricts the availability of civil servants and the authority to hire staff locally. Politicisation of civil servants, including teachers, and a centralised mindset severely limits the capacity of the federal government to realign structures, readjust positions and deploy government employees to provincial and local levels. The latest readjustment plan reveals the concentration of more staff at the federal level and an insignificant allocation of employees at the provincial level. At the local levels, the population size of the municipality determines the number of employees. That means, municipalities with small populations but in need of qualified staff are left on their own to meet their social and development goals.

Impact on school safety intervention:

The population of the municipality determines the size, level, quality, commitment and incentives for public servants. Since the federal government does not seem to encourage the outsourcing of public services to non-government organisations, the new structures attempt to deliver services on its own. That means the (education) projects’ counterpart agencies will differ between areas regarding availability, knowledge, and skills. Staff transfer remains high in the municipalities and government offices with high work pressure and less opportunity. This causes the projects to begin from the scratch while coordinating with government agencies. Besides, the number and level of government staff at local levels vary by the population size of the specific municipalities. That means, partner municipality with less population will have to survive with less number and mid-level staff. So, the lack of adequate and skilled human resources can affect the timely implementation and quality of deliverables under the SIP and DPRP in target schools and municipalities. But, the project has to allocate more resources and staff inputs to ensure quality in coordination and effectiveness in municipalities with an inadequate number and transfer of government staff besides school teachers, preferably the head teacher.

Mitigation strategy:

Assess the capacity and offer technical support in improving the performance of partner municipalities and schools. Population size, social and political culture, fund flows and management trends, as well as number and qualification of human resources in partner municipalities and schools, determine the quality of cooperation and operating environment for the project. Assessment of target municipalities and schools concerning financial and human resource availability and management can help in devising appropriate communication and partnership strategies that best meet the preconditions for project’s success. Similarly, the capacity and performance assessment also help in identifying the areas where projects can provide technical support to improve organisational capacity in the partner schools and municipalities. So, it is recommended to monitor the internal and external fund flows as well as qualification and number of teachers and staff in the schools and municipalities to understand the importance of school safety, integrate into their policy priorities, allocate resources and take ownership to implement. Having an efficient government counterpart not just reduces the burden on the project but also increases the likelihood of success and sustainability.

3.4 Hamonisation of new systems

Numerous policies, laws, directives, procedures and standards are to be prepared, revised, endorsed and applied. Similarly, structures at all three levels of the federal system need to be restructured or revived. Government employees need to be readjusted and deployed. Policy, legal and financial regulations have to be standardised. Once the availability of structures, policy and legal guidelines and civil servants are dealt with, an enormous amount of resources and efforts is still required to ensure that they are endorsed, implemented and are fully functional in line with set standards, complying with minimum regulations, and delivering public goods. Learning from past experiences in Nepal shows that just having a policy guideline, sufficient employees, a sound budget and clear mandates do not guarantee accountability, transparency and quality in public services. A couple of robust institutional mechanisms, at all three levels, have to work in a harmonised way to provide backstopping, and guidance to comprehend and practice new policy and legal arrangements. Similarly, transparent and robust compliance and scrutinization processes have to be oriented and followed at all public institutions under the new system.

Impact on school safety intervention:

Lack of coordination and participation in federalising the country, and the education sector, in particular, tend to produce smart policy guidelines and structural frameworks, but do not necessarily build local ownership. The absence of adequate human and financial resources at the provincial and local level affect timely planning, implementation and compliance with applicable legal, policy and financial regulations. As a result, non or poor compliance with federal (for now) standards affects fiscal transfer and other monetary incentives to local and provincial levels. On the other side, provincial and federal governments determine the conditions and compliance requirements without adequate support, in terms of staff, time, and resources, at the local level to perform as expected. The poor performance of partner municipality and schools also affect their qualification to attract regular and more funds from provincial and federal governments. The projects may face high expectations compared to the resources it has to meet the needs of the counterpart municipality or school. The poor performance of municipalities impacts on the regulatory efforts of the SMCs and increases the risk of corruption or manipulation of project resources for non-project priorities. The uncertainty about the capacity of partner government agencies, including municipality and schools, will impact the project during 2018-2019 more significantly. However, such impacts will not be significant but are likely to slow the implementation and achievement of quality outcomes in most of the schools, if a generic approach would be adopted.

Mitigation strategy:

Assist in the adoption, implementation and harmonisation of education related policy practices in partner provinces, municipalities and schools. As federalisation process is not as participatory as it should be, there will be times when policy priorities of different federal units contradict with one another. Constitutionally, the local level legal and policy provisions should not contravene with provincial level government and province should not challenge the policy provisions of the federal government. Projects can take this as an opportunity to support the education-related (with focus on school safety) policy and law drafting and enactment process in partner provinces, municipalities and local levels ensuring that they do not overlap or contradict as required by the law. Similarly, support the government counterparts in preparing and implementing other supplementary policy directives can also benefit the project by integrating its components in governments’ priorities. This also reduces the risk of dealing with various policy provisions for the same project in different areas as well as build synergy across components and partners

3.5 Politicisation of development assistance

The federal government is reviewing its legal and policy arrangements to deal with foreign assistance. While provincial and local level governments are prohibited from directly contacting or receiving foreign aid without prior approval from their federal counterpart, a clear policy directive is yet to come. In the meantime, some provincial governments have started developing their own criteria, conditions and arrangements for seeking and managing aid in their jurisdictions. The federal government is advised to review its Development Cooperation Policy, 2014, and impose stringent requirements on foreign assistance. The conditions include prior approval from the federal government in selecting and implementing development projects, listing 8 priority areas for funding, channeling funds through government systems that are on-treasury, setting up federal, provincial and local level ‘project banks’, and phase-wise support strategies.

There is also a shift in foreign assistance. Loans and technical support are increasingly taking over from grants. Furthermore, the government is providing incentives and comfortable conditions for foreign aid mobilised under the government system, whilst enforcing various conditions upon those mobilising funds outside the formal route. However, the spending capacity of the public sector is deteriorating despite having more funds. The role of line agencies and the SWC is uncertain in regulating and managing development projects. Despite having a standard procedure to select working areas, partners and modalities, the leaders and officials at counterpart line ministries can play a decisive role in altering or imposing priorities and processes.

Education is a priority sector for foreign assistance. As a result, the Ministry of Education attempts to provide necessary policy support for channeling funds in the education sector. The Department of Education (DoE), which is the implementing agency for education policy and guidelines in addition to maintaining standards and coordinating with other government departments and local level authorities, will be dissolved. A capacity building unit in MoFAGA will take over the responsibility of building the capacity of education-related stakeholders at provincial and local levels. It is yet to be certain whether or not or to what extent provincial level ministries, such as Ministry of Social Development and Ministry of Economic Affairs and Planning, get a direct role in regulating foreign assistance in areas such as education, disaster and health.

Impact on school safety intervention:

There is a lack of clear understanding, and agreement among federal units, over federalising or centralising development assistance. The struggle between federal units to seek control over development aid will affect a smooth operating environment for the projects. Some projects may have donor’s support and blessing to overlook the government’s regulation as faced by others, there are emerging practices in some provinces and local levels busy in preparing policy conditions to register and align externally-funded projects in the respective agencies. If not synchronised with the federal regulations managing foreign assistance and/or vice versa, projects have to follow additional rules and standards to satisfy multi-layered compliance and reporting requirements. It is least likely that government will force to channel technical assistance through on-budget and on-treasury in coming years, but easing regulations to projects implemented through public sector will undoubtedly be a lucrative option for donors. Working with and through government system have advantages and risks that vary across provinces and municipalities. At the moment and with the current working modality of working ‘with’ government systems is likely to have an inconsequential impact on the project. However, the future arrangement of managing foreign assistance in general and technical assistance, in particular, will have to thoroughly analyse to assess the impact on the project management and outcomes.

Mitigation strategy:

Correspond the project with local priorities while communicating with multiple layers. Having a clear line of communication with the Department of Education may have helped smooth the inception activities, but the field-based implementation has to be coordinated with additional agencies at federal, provincial and local levels as deemed necessary. Different agencies and federal units are likely to have diverse priorities and regulations, at least in the beginning of federalisation. A regular and clear line of communication needs to be maintained at all levels, to avoid confusion and any inter-department or inter-governmental disputes or rivalry. The endorsement of the new development framework, or the revised version of Development Cooperation Policy 2014, can affect the projects but it takes time. In another word, federal, provincial and local level governments will need time and series of agreements before the changes in development assistance take into effect. To avoid any severe interruption, it is recommended to resemble the project components with local level priorities of counterpart province, municipality and schools. Although the agreement with federal authority can ease approaching the provincial and local level authorities, the local ownership and commitment are required to ensure enabling and coherent working conditions at the local level. It is, therefore, essential to align the project components with local level priorities, seek the ownership of local actors by supplementing with their organisational mission and requirements, and ensuring their participation in the project implementation. Furthermore, project should remain vigilant of limited scope in governing the management, resource use and outcomes of the project if shifted to work ‘through’ government system at a later stage. A series of procedures will have to be followed in addition to risk assessment.

Conclusions

The assessment is aimed at reviewing the federalisation process in Nepal, assessing potential impacts on the school safety project, and recommending mitigating strategies. The assessment is based on a literature review, including literature (e.g. policy, law, constitution, progress report, performance review, budget speech and analysis) from government ministries, departments, experts and practitioners on federalism, state restructuring, the education sector, foreign assistance and social development. The assessment is divided into two parts; federalism in Nepal, and alignment of school safety project with the federal system.

Federalism is a new concept for Nepal. Federalism is considered a better governing system which is more participatory, accountable and has greater promise for realising local potential. Nepal’s federal system comprises 7 provinces and 753 local levels. Powers are constitutionally shared between federal, provincial, and local levels. The exclusive and concurrent powers are divided between each of the units with the residual power limited to the federal government. Restructuring of the country highlights the strengths, potentials, and capabilities of Nepal, as well as the challenges of underdevelopment, and widespread poverty.

The education sector is one of the essential services that has to be federated as smoothly and as early in the process as possible, considering the implication of delays to the future of millions of students around the country. The federalisation of the education sector also needs to bear in mind the challenges it faces and look for ways to deal with those in a new context. Politicisation, sub-standard quality, non-compliance with regulations, corruption, privatisation, inadequate infrastructure, and an outmoded and intransigent teaching and learning environment are some of the common problems school education in Nepal suffers from. A shrinking national education budget, coupled with insufficient foreign assistance, won’t help improve the quality of education in Nepal. Vulnerability to natural disasters adds another layer of complexity to the education sector. Some initiatives are helping the federal government to cope with the challenges of school-level education, including school safety, but a wide gap is evident at provincial and local levels.

Clashes over jurisdiction between federal units, conflict over resource allocation and distribution, the capacity of new structures to deliver services, the implementation of new policies and structures, and the politicisation of foreign assistance are major five areas that impact the school safety intervention. To mitigate the negative impact of federalism, five strategies are recommended: monitor the fund flows and allocation; assess the capacity and offer technical support; assist in the adoption, implementation and harmonisation of education related policy practices; and correspond with local priorities while communicating with multiple layers.

A clear line of communication, frequent interaction, transparent project management, and pro-active engagement on policy, programme and budget formulation and implementation will not just minimise risks, but also increase the opportunity for the school safety projects to lead the way in delivering sustainable improvements to school safety across Nepal.

(The article forms an integral part of a political economic analysis I provided to a DFID-contracted Nepal Safer School Project, August 2018)

————————————————————————————————————-

[1] School safety refers to three inter-related components: safer learning facilities, school disaster management, and risk reduction and resilience education.

————————————————————————————————————————-

References

FCGO, 2017. Consolidated Financial Statement- Fiscal Year 2015/16. Kathmandu.

GON, 2015. The Constitution of Nepal 2015. Nepal Law Commission.

GON, 2017. Local Government Operations Act 2017 (LGOA). Nepal Law Commission.

GoN, 2018a. Disaster Risk Reduction National Strategic Action Plan (2018-2030). Kathmandu.

GoN, 2018b. National Disaster Risk Reduction Policy, 2074 (BS).

INFORM, 2018. Country Risk Profile for Nepal, 2018.

MoE, 2017. Nepal Education Sector Comprehensive School Safety Master Plan. Kathmandu: Ministry of Education.

MoEST, 2017. Report of the High-Level Working Group to Recommend Improvement in Education Sector, 2074 (BS), Annex 6. Kathmandu.

MoF, 2017a. Development Cooperation Report FY 2016-2017, Kathmandu, Nepal. P.14

MoF, 2018a. Economic Survey FY 2074/75 (BS). Kathmandu

MoF, 2018c. Education Sector in Aid Management Platform, assessed on 10 July 2018, http://amis.mof.gov.np/portal/.

NPC, 2015. Post Disaster Needs Assessment, 2015. Kathmandu.

OPMCM, 2017. Unbundling/Detailing of List of Exclusive and Concurrent Powers of Federation, the State and the Local Level, Provisioned in the Schedule 5,6,7,8,9 of the Constitution of Nepal, Report submitted to the Federalism Implementation & Administrative Restructuring Committee. Kathmandu.

UN, 2018. Nepal: Administrative Unit Map. Kathmandu.